Related story

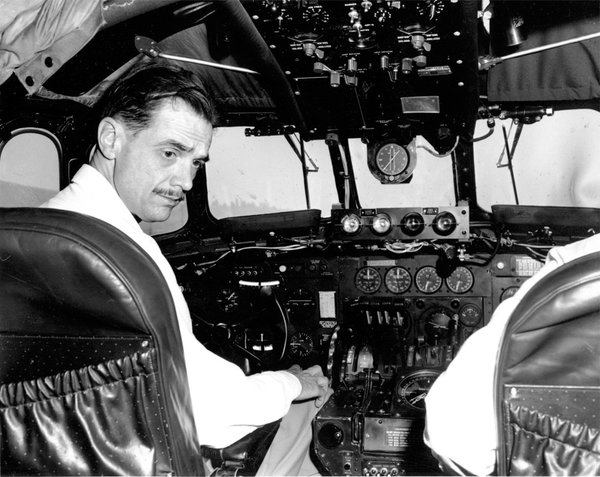

Howard Hughes was one of the wealthiest men in the world.

Born the heir to a drill-bit fortune, Hughes expanded his empire over several decades, building airplanes, contracting with the government and buying casinos on the Las Vegas Strip.

The characters: Howard Hughes

Born the heir to a drill-bit fortune, Hughes once was the wealthiest man in the world. In his early years, he ran his father’s business, Hughes Tool Company, and used it to acquire other enterprises, including a movie studio, two airlines and vast real estate holdings. Later in life, Hughes became reclusive, holing up in his bedroom, writing memos to his aides and reportedly living in filth. On Thanksgiving Day 1966, he arrived by train in Las Vegas and moved into the Desert Inn, where he stayed for four years. While in Las Vegas, Hughes never left the hotel — he never even opened the drapes in his room — but nevertheless bought the Desert Inn and five other Strip properties.

The characters: Bob Maheu

Known as Hughes’ alter ego, Maheu was the face of the reclusive billionaire during Hughes’ years in Las Vegas. Politicians, businesspeople and other government officials met with Maheu and considered him a direct representative of Hughes. Maheu never actually met Hughes; instead, the men communicated via written memos and talked on the telephone. Before working for Hughes, Maheu did counterintelligence work for the FBI during World War II and also for the CIA, including working on a plot to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

He was an earlier iteration of the billionaires running the world today. And just like today’s billionaires, Hughes wasn’t afraid to use his vast empire to get what he wanted. Money and power shaped politics back then, and it shapes politics today, perhaps to an even larger degree.

In Hughes’ days, dropping off a briefcase or two stuffed with campaign contributions was legal. There weren’t supposed to be strings attached to the money, but there often were. A generous sum would, at the very least, buy the ear of a politician.

“He wanted things his way, and he was willing to get things his way no matter what it took,” said Peter Maheu, the son of Hughes’ right hand man, Bob Maheu. “He had no problem paying for what he wanted.”

Hughes was indiscriminate about whom he gave to. He gave to Republicans; he gave to Democrats. No matter who was in control, he wanted control over them.

Eventually, one of Hughes’ donations brought down President Richard Nixon by inspiring the paranoia that culminated in the Watergate scandal.

Among the matters that Hughes fretted over: haggling with the Atomic Energy Commission to delay atomic testing in Nevada, competition from other casino owners on the Strip and whether Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun was an ally.

They speak to Hughes’ attentiveness to the world around him, even as he withered in his penthouse on the top floor of the Desert Inn hotel, and the great lengths he was willing to go to manipulate anyone and anything to get his way.

Here, we take a look at memos exchanged by Hughes and Maheu that detail the ways Hughes used his influence to change the course of history. Until recently, the memos had been locked for decades in Greenspun’s safe.

Hughes on atomic testing

Hughes was a war hawk. After all, he was a defense contractor.

But there was one defense project Hughes despised: the atomic tests.

It wasn’t general opposition to the tests. Detonate bombs in the Pacific? Fine. In Alaska? Great. In Las Vegas? Not in Hughes’ backyard.

From his Desert Inn penthouse, Hughes watched preparations for atomic testing play out on TV, his only window to the outside world.

“I have been thinking about this bomb deal,” Hughes wrote to Maheu two days before the 1.3-megaton Boxcar nuclear test was scheduled to be conducted north of Las Vegas. “We are making a hell of a case, but I am afraid we are not even close to a cancellation. Now I heard on Ch. 3 that the A.E.C. (Atomic Energy Commission) claims we were invited to a briefing a month ago, at which time we would have had an opportunity to object.”

Hughes, through Maheu, fought hard to stop the test. He hired teams of scientists to sound warning bells about the dangers of nuclear testing, tried to persuade a competitor to join forces with him and personally appealed to the White House. In a last-ditch effort, Hughes asked Maheu to negotiate with the AEC and threaten a public relations campaign against atomic testing if the commission went forward with Boxcar.

“I urge we point out to the A.E.C. that, after this uproar and public exposure and after the fears and curiosity of the public have been aroused, the entire situation, not only in Nevada, but throughout the nation is going to be highly explosive,” Hughes wrote. “It will only require a leader. I could easily be that leader.”

Hughes wanted a 90-day moratorium on any tests bigger than 1 megaton. Hughes hoped that during that time period, the AEC would further evaluate the potential adverse effects of testing, including impact on water supply, radioactive contamination and earthquakes.

“So, Hank (Greenspun) points out: Who is to say it will not be discovered later that detonating bombs under ground (sic) and poisoning and adulterating the earth for all the future of mankind is not equally as dangerous as an explosion in the air,” Hughes wrote. “One thing is sure — extra sure — if they shoot that bomb on Friday, nobody but nobody can go back and undo it.”

The AEC, however, remained stalwart, asserting in a written statement the needs of national security and detailing the precautions taken to contain radioactivity — a statement Hughes called “pure 99 proof unadulterated (expletive).”

Hughes positioned himself as a man of the people; he would echo the concerns of scared housewives dropping dishes, losing their appetites and shaking in fear.

“There were a lot of people who didn’t like the testing,” Peter Maheu said. “When he spoke, he spoke with a heavier voice.”

But Hughes was no ordinary person. He was a man with unlimited access and resources.

“I am sure you should personally go to the White House after we have obtained the 90-day delay and endeavor to sell the President on a permanent policy,” Hughes wrote to Bob Maheu.

The image of Las Vegas under siege was antithetical to Hughes’ starry-eyed vision of the city, and Hughes wanted to create the perception that the tests would jeopardize Las Vegas’ resorts. People should come to relax in Las Vegas, a place “where they can forget the war, the draft, and they will not encounter any violence,” not to be reminded of the possibility of an imminent nuclear attack by the Soviet Union, Hughes wrote.

“This is a hell of a note in a place that is being developed as a resort, which depends for its very life-blood on the tourists who come here voluntarily in open competition with Hawaii, and the many, many other resorts,” Hughes wrote.

In the days before the tests, he scribbled off furious memos to Maheu, telling him, “I don’t want you stopping your work on the bomb to write me reports.”

The 90-day delay never came. On April 26, 1968, Boxcar was detonated in the northwest corner of the Nevada Test Site. It was one of the biggest blasts in the site’s history.

Years later, Hughes scored a victory with Nixon, who agreed to limit all tests to less than 1 megaton. The end of nuclear testing at the Nevada Test Site didn’t come until 1992, 16 years after Hughes’ death.

Hughes on Hank Greenspun

The characters: Hank Greenspun

Greenspun was editor and publisher of the Las Vegas Sun from when he bought the paper in 1950 until his death in 1989. Greenspun also was involved in real estate, developing Green Valley in Henderson. During Hughes’ time in Las Vegas, Greenspun sold Channel 8 to the billionaire.

To advance his anti-bomb agenda with the public, Hughes needed a strong ally. A local voice. Who better than the outspoken publisher of a Las Vegas newspaper?

Greenspun was a friend of Maheu who already had shown strong support for Hughes. In a December 1966 column shortly after Hughes arrived in Las Vegas, for example, Greenspun praised the billionaire as a “man who stands foremost among all giants of industry, finance and humanity.”

“He alone is bigger than any other single Nevada industry or combination of all,” Greenspun wrote in the Sun.

Hughes thought Greenspun was important, too, particularly when it came to the atomic tests. Hughes told Maheu in a memo that he had read the Sun and was unable to detect any partisan bias. In fact, he said, the Sun appeared to be staying “immaculately uncontaminated” by refraining from getting directly involved in the bomb debate.

Did Maheu agree, Hughes wondered? And what could the two of them do “to persuade Mr. Greenspun to jump in and get wet all over?”

Hughes begged his lieutenant to obtain Greenspun’s “all-out unlimited support.”

“I am positive, from his past editorials, that this is 100% his kind of a battle, and it is a cause close to his heart,” Hughes wrote. “I am sure he will make a real crusade out of this if we encourage him.”

Greenspun had a reputation for using his front-page “Where I Stand” columns to push his views on issues. Hughes, via Maheu, needed only to make sure that Greenspun was on their side on this issue.

He was. Greenspun wrote critically about bomb tests, much to the delight of Hughes.

“Please call Hank if he is awake and tell him I just read his column and I seriously think he ought to get the Nobel Prize for it, it is that great!” Hughes wrote to Maheu. “Now that Hank has allied himself with us I don’t think we should leave any smallest stone unturned.”

Hughes also tried to buy Greenspun’s media holdings, including the Sun, but Greenspun declined to sell them.

But Greenspun remained sympathetic to Hughes, Maheu told his boss.

“You may rest assured that he will never mention your name other than in a favorable light,” Maheu wrote. “(Greenspun) has been an admirer of yours for years and he truly believes that your mere residing in the area is a great contribution to the state.”

Brian Greenspun said his father and Maheu were close friends; they trusted each other. Peter Maheu described Hank Greenspun as “probably as a good a friend as Dad had” in Las Vegas.

That friendship eventually contributed to Greenspun professing a far less favorable view of Hughes. When Maheu was ousted from the Hughes organization, Greenspun took his friend’s side and questioned whether the billionaire actually chose to leave Las Vegas. And Greenspun, like Maheu, cast doubt on whether the people who succeeded Maheu were rightful heirs to the Hughes empire.

Greenspun also criticized Hughes on other fronts. In a column, he wrote that while he initially believed Hughes’ entry into the Las Vegas casino market would be good for the community, a time came when he had to decide whether Hughes “had gone too far” in acquiring casinos. Greenspun decided that Hughes’ influence threatened “the orderly development of the area,” so he “voluntarily got off the bandwagon.”

“I also felt that I had prostituted my newspaper in Hughes’ interest sufficiently, and would have no more of it,” he wrote.

Greenspun also fought with the Hughes organization in court.

One dispute involved a $4 million loan Hughes gave Greenspun to help the Sun recover from a fire that destroyed its offices. Hughes’ company later sought to cloud the title Greenspun had to some 2,000 acres of land, which Greenspun had used to secure the loan. Greenspun prevailed in court and that land now is part of Green Valley, a master-planned community developed by the Greenspun family’s American Nevada Company.

Another court battle involved the Hughes company’s decision to withdraw all advertising from the Sun. Greenspun argued it was retaliation for negative coverage and violated antitrust laws, but Hughes’ company won in the end.

Hughes on Bill Harrah

The characters: Bill Harrah

One of the most influential figures in gaming history, Harrah founded and ran two casinos in Northern Nevada.

Maheu and Hughes also discussed Bill Harrah, the Northern Nevada casino operator. Hughes made serious moves to acquire Harrah’s properties.

In a March 1, 1968, exchange, Maheu wrote that he had just spoken to Harrah using a script Hughes suggested. Maheu called Harrah “undemonstrative” but said he felt they had reached a “deal subject to mutual agreement on the numbers.”

Hughes did not respond to that point; instead, he cautioned Maheu not to tell gaming regulators anything about their Northern Nevada plans.

Six days later, Maheu was seething. Harrah, he said, had put forth a proposal that was such a “complete shock,” Maheu wanted to end the deal.

“I personally think we should tell Mr. H. to go to hell,” Maheu wrote. “Dealing with him seems to be a continuous study in the act of ‘opening surprise packages.’ ”

Noting some undesirable demands imposed by Harrah, including an “obvious desire to compete with us across the street utilizing the equity in the name Harrah,” Maheu told his boss he was forced to conclude that Harrah was “completely out of his (expletive) mind.”

To settle the matter, Hughes urged Maheu to get help directly from the governor. Maheu was to tell Paul Laxalt that Harrah’s demands made their negotiations “all the more tragic,” because nobody else could match what Hughes was offering.

Hughes never acquired any of Harrah’s properties.

Hughes on Kirk Kerkorian

The characters: Kirk Kerkorian

The billionaire casino mogul built some of the largest hotels on the Strip and created the company that today is MGM Resorts International. Hughes and Kerkorian in many ways led parallel lives. Kerkorian bought and ran the MGM movie studio, flew planes during World War II and ran a small charter airline.

Of all the men in Las Vegas’ gaming industry at the time, none was more powerful than Kirk Kerkorian, who created a casino kingdom that grew into today’s MGM Resorts International.

During Hughes’ era, Kerkorian was focused on building the world’s largest hotel: the International. Hughes was threatened by grand visions of the resort, but in April 1968, Maheu devised a plan to use Kerkorian as an ally in Hughes’ fight against atomic testing in Southern Nevada. Maheu would tell Kerkorian that Hughes would not embark on a planned 4,000-room expansion of the Sands because of concerns about the tests.

Hughes, who often referred to Kerkorian as “K,” embraced the scheme. But he said it must be kept a close secret, and rather than get Kerkorian to come right out and say he was halting the International too, they should convince him to make a veiled threat instead.

“You might even tell K. that if he will come out with a statement … that he is worried about the blasts, I would simultaneously say that is the reason we stopped the Sands,” Hughes wrote in April 1968. “I think it would be a mistake to try to persuade him at this early stage to cancel his building program. I think that for now we should concentrate simply on persuading him to join with us in protesting these new tests, and in saying he is worried for the International because of its extreme height.”

Hughes never got Kerkorian to join in his anti-bomb campaign.

Also in April 1968, Hughes told Maheu to prepare for a “blockbuster.” Hughes had proposed an airport project but was beginning to have serious doubts and was frustrated that the International would stand in the way of people traveling from the airport to Hughes’ cluster of hotels. Hughes said he was flirting with the idea of exchanging the Stardust for the International but agreeing not to complete the latter project.

He knew it was a risky plan, but he wanted to keep the International from falling into the hands of a competitor.

“So, we will probably have to persuade K to stop it gradually before he delivers it to us,” Hughes wrote. “Let’s not cross that bridge until we first decide if any part of this plan is do-able. I know one thing — I may not live to see that airport completed. I would like to spend that effort on removing the International in one way or another and then spend the rest of my life under just a little bit less tension.”

Hughes also directed Maheu to use the International plan as leverage in Hughes’ quest to acquire the Stardust. Maheu should tell officials that buying the Stardust, as well as the Silver Slipper, would not be an expansion of Hughes’ casino empire because he’d be trading the Stardust for the unfinished International. Hughes said Maheu should tell officials his organization would be “quite happy” to maintain the position they were in after earlier gaming licenses were granted.

“Unfortunately, this is not possible, because the Commission has given a building permit to the International Hotel which is going to change the entire complexion of the Strip and alter completely the relative position of our holdings and the holdings of others,” Hughes wrote. “Certainly the right to add Slipper (and) Stardust to our present holdings will leave us in no stronger position, after the addition of International and possibly (Circus Circus) to the area.”

Hughes never was able to get his hands on the Stardust. The Justice Department, under President Lyndon Johnson, blocked the sale because it violated federal antitrust rules.

But that proved to be only a roadblock in Hughes’ Strip ambitions: Once Nixon moved into the White House, a more cooperative Justice Department allowed Hughes to acquire the Landmark.

Hughes on Vice President Hubert Horatio Humphrey

The characters: Lyndon Johnson

The 36th president of the United States, Johnson was in office during the first three years Hughes lived in Las Vegas. Hughes made a personal appeal to Johnson, in the form of a written letter, to try to convince him to stop atomic testing.

The characters: Hubert Humphrey

Johnson’s vice president, Humphrey had a relationship with Hughes through Maheu. During the height of atomic testing in Nevada, Hughes tried to use Humphrey to stop the tests.

“There is one man who can accomplish our objective thru Johnson — and that man is H.H.H. Why don’t we get word to him on a basis of secrecy that is really, really, reliable that we will give him immediately full, unlimited support for his campaign to enter the white House if he will just take this one on for us?”

Hughes on President Lyndon B. Johnson and Humphrey

“You know I am perfectly willing to write a short personal message to Johnson, which we could ask Humphries to deliver — hand deliver — to Johnson. ... There is only one bad thing, if Johnson sends a message back that he wishes he could, but, due to the shortness of time, etc., etc. — If that happens, we really have had it but good. After that, nobody would touch it.”

Hughes on Nevada Gov. Paul Laxalt and Richard M. Nixon (then a presidential candidate in 1968)

The characters: Paul Laxalt and Richard Nixon

The governor of Nevada from 1967 to 1971 and a U.S. senator from 1974 to 1987, Laxalt had a close relationship with Hughes. The 37th president of the United States, Nixon resigned in 1974 after the Watergate scandal. A loan from Hughes to Nixon’s brother, Donald, hurt Nixon in two previous elections.

(Hughes repeatedly referred to Humphrey as “Humphries”)

“I want you to go to see Nixon as my special confidential emissary. I feel there is a really valid possibility of a Republican victory this year. If that could be realized under our sponsorship and supervision every inch of the way, then we would be ready to follow with Laxalt as our next candidate.”

Hughes on Jay Sarno

The characters: Jay Sarno

The entrepreneur who founded Caesars Palace and Circus Circus. Hughes briefly considered acquiring Circus Circus.

It’s unclear what Hughes hoped to accomplish with Jay Sarno, the flamboyant businessman who built Caesars Palace and Circus Circus. But Hughes at one point tried to convince a Las Vegas Sun columnist to embarrass Sarno.

Hughes told Maheu that he should get columnist Paul Price “on the trail of ‘Wild Man Sarno.’ ” Hughes had a hunch that, because Price felt that “violence and brutality and threats have no place in a casino,” Price would find a lot to dig into with Sarno.

“Maybe you should just persuade Price to interview Sarno, with you absent, and to tell Sarno he (Price) has some misgivings about the desirability of the Circus, or what ever (sic) type of remark is necessary to trigger Mr. Sarno off so that the ‘Wild Man’ will start raving and ranting and baring his teeth and threatening dire destruction to all who get in his path,” Hughes wrote. “If Sarno would just put on one of his standard performances in front of Price, we would have it made.”

Elsewhere, Hughes referenced the possibility of acquiring Circus Circus, but that never happened.

Hughes on racism

Aside from competition, aside from germs, aside from the outside world in general, there was another aspect of society Hughes feared deeply: racial progress.

Hughes reiterated his racist views to Maheu. In the midst of the riots after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Hughes wrote that while there was tremendous pressure on Strip owners to accept a “more liberal attitude toward integration” and civil rights, he would not stand for it.

“I can summarize my attitude about employing more negroes very simply — I think it is a wonderful idea for somebody else, somewhere else,” Hughes wrote. “I feel the negroes have already made enough progress to last the next 100 years, and there is such a thing as overdoing it.”

The Strip

To Hughes, the Strip was unconquered territory — and he was determined to rule it all.

Hughes snuck into Las Vegas under cover of darkness on Thanksgiving 1966, slipping into the top floor of the Desert Inn. Before long, he purchased the entire resort. Then another, and another. And so on.

He did it all from within the confines of his penthouse, a self-made prison from which Hughes didn’t emerge until he left Las Vegas for good.

Despite never having met them face-to-face, Hughes had strong opinions about the other casino figures of his day.

In the end

In the end, Hughes didn’t always get his way. Atomic testing didn’t stop in Nevada until 1992. Hughes had to pay back shareholders for money they lost when he acquired Air West. And as much as he hoped that buying politicians meant he always would get his way, he didn’t.

At the same time, Hughes accomplished an astounding amount, snapping up six properties on the Strip without ever having to appear before the Gaming Commission, acquiring vast land holdings that later would become Summerlin and playing political chess with the country’s top lawmakers.

Hughes accomplished things no other man could have. What the world didn’t know was that as he did it, he sat naked in a dark hotel room, hair stretching down his back and fingernails long, watching movies and collecting his urine in bottles.

The illusion of Hughes — the money, the power and the charisma of his youth — was enough. Everyone believed in Hughes, or perhaps his money, enough for him to play the role of most powerful man in the world to his last day.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy