WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump visited the Tennessee estate of Andrew Jackson last month to symbolically claim the mantle of the first genuinely populist president since the 1830s. Just like Jackson, Trump defeated a political dynasty to take power and was now determined to challenge what the new president called “the arrogant elite.”

But last week suggested the limits of the comparison. Where Jackson made it his mission to destroy the Second Bank of the United States, which he viewed as a construct of the nation’s wealthy to wield power over the people, Trump saved the Export-Import Bank and signaled that he may preserve the leadership of the Federal Reserve, two modern-day tools of federal power in the economy.

As he nears 100 days in the White House, Trump has demonstrated that while he won office on a populist message, he has not consistently governed that way.

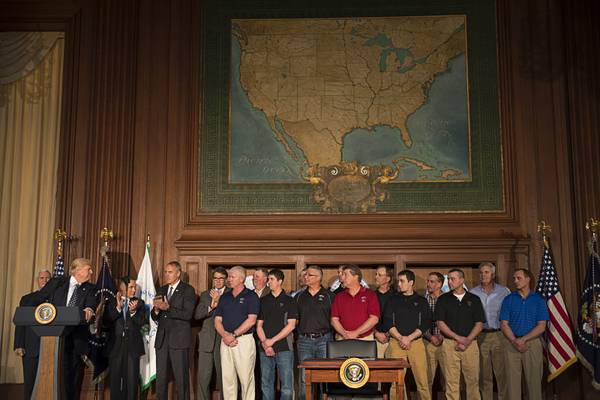

He rails against elites and on Tuesday signed an order favoring American companies for federal contracts. But he has stocked his administration with billionaires and lobbyists while turning over his economic program to a Wall Street banker. He may be at war with the Washington establishment, but he has drifted away from some of the anti-establishment ideas that animated his campaign.

The shift comes as the president has moved to marginalize their most outspoken proponent, Stephen K. Bannon, the White House chief strategist who made it his mission to deconstruct “the administrative state.” On the rise are Jared Kushner, his son-in-law and senior adviser, and Gary D. Cohn, the former Goldman Sachs president serving as the president’s national economics adviser.

Much of this has stoked dismay among the conservative populists who saw Trump as a once-in-a-lifetime figure.

“Stay true to populist nationalism, sir,” Patrick Howley, who worked for Bannon at Breitbart News, wrote in a recent open letter to Trump on The American Spectator’s website. “I know you believe in it. It carried you over the goal line in the Midwest to victory.”

“If you abandon populism,” he added, “then you will not really have any constituency anymore. Will you be an establishment Democrat? Will you be a neocon? How will people even think of you? You will be adrift.”

Ned Ryun, founder of American Majority, which trains political activists, said Trump’s core supporters were watching. “There’s definitely some concern that’s starting to grow,” he said. “I do believe that Trump has some populist beliefs and undertones himself. But he has to have Steve Bannon whispering in his ear saying, ‘Hey, stick with these ideas; these are winning ideas.'”

Even some of Trump’s friends worry that he has gotten away from the policies that fueled his success in the campaign. “He ran as a populist but so far has governed as a traditionalist,” said Christopher Ruddy, chief executive of Newsmax Media.

Ruddy praised the president for using his bully pulpit to push companies to keep jobs in America but said his health care plan pushing millions off Medicaid was not true to his roots. “They might break out and do some more populist stuff, but I wouldn’t call his presidency so far populist.”

That may underscore just how much Trump’s populist frame was the inspiration of Bannon in the first place. It was Bannon who suggested the comparison to Jackson, whose painting now hangs in the Oval Office.

Trump, after all, was always an unlikely populist, a self-proclaimed billionaire with a private plane and gilded estates. Trump, who by one count switched political parties seven times before last year’s campaign, seems less driven by ideology than by instinct borne out of his own resentment of elites who, in his view, have never given him the respect he deserves.

“Bannon gave him a worldview to sink those emotions into, to connect those emotions into,” said Michael Kazin, a historian at Georgetown University and author of books on populism and William Jennings Bryan. That does not make Trump the second coming of Jackson, he added. “The only comparison, as Bannon knows, is there’s a toughness, there’s a running against the entrenched, educated elite. That part’s true.”

Trump’s election, coupled with the British referendum to leave the European Union and the rise of anti-establishment parties in Europe, has focused renewed attention on the power of populism in Western societies. Authors have rushed out a shelf full of books, and contracts for more are still being signed; universities and think tanks are awash in panel discussions.

Populism can be found on the political right and left, often fueled by economic disparities, a sense of dislocation and anger at elites. In the United States, populism after Jackson gained steam in the 1890s with the formation of the People’s Party and Bryan’s presidential campaigns. It was revived in the 1930s by Huey Long and his Depression-era Share the Wealth Clubs and had a brief return in the 1990s with Ross Perot’s independent campaigns.

While populists have rarely won the White House, they prodded those who did, like Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt, who enacted progressive policies expanding government power over the “malefactors of great wealth,” as the first Roosevelt put it. On the other side of the spectrum,Richard M. Nixon appealed to the “silent majority,” while Ronald Reagan was boosted by aggrieved working-class Americans who abandoned the Democrats.

Trump did not have a monopoly on populist appeal last year. His analog on the left was Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who ran a Wall Street-bashing campaign for the Democratic nomination. While the two share a loathing for free-trade agreements and support for expansive spending on new roads and bridges, Sanders said the opening months have shown Trump to be a “right-wing extremist,” not a populist.

“You’re not a populist if you want to, as he did in his health care bill, raise premiums for low-income senior citizens,” Sanders said in an interview. “You’re not a populist when you want to throw 24 million people off health care. You’re not a populist when you want to do away with nutrition programs for pregnant women and children.”

It may be as much about attitude as policy. Trump’s program may favor corporate interests, but he uses Twitter to call out and threaten companies for building plants overseas. He may be helping coal companies by rolling back President Barack Obama’s clean power rules, but supporters see him taking on environmentalists, regarded as a privileged class with little care for the effect on jobs. His budget cuts may ratchet back or eliminate programs that help supporters, but they see him confronting a government grown bloated and unaccountable.

“His appeal was definitely populist and his rhetoric remains so, but the reality of how he’s governed has been more of a rich-person conservative with feints toward his populist base,” said Sheri Berman, a Barnard College political-science professor who has written about populism. “There’s this split between rhetoric and reality for those who are paying attention to the details, which of course most voters have neither the time nor the energy to do.”

It may be that nationalist is a better description. “As long as he does his hard-line stuff on immigrants, he’s going to hold onto a lot of those people,” said John B. Judis, author of the new book “The Populist Explosion.”

Trump may not succeed in rebuilding the manufacturing sector or winning trade wars with China, Judis added, but they want to see him trying. “If we don’t have another downturn for the next three or four years, he’ll keep his support.”

Richard D. White Jr., the business school dean at Louisiana State University and author of “Kingfish: The Reign of Huey P. Long,” said Long would have seen Trump as an example of the plutocrats he spent a lifetime battling. But what they have in common, he said, was a pugilistic approach to politics that touches a chord with many constituents.

“Probably the best word to define it is ‘anger,'” White said. “There’s an anger in the people, whether it’s Huey Long or Andrew Jackson or Donald Trump. Populism feeds on that anger, and astute politicians can take advantage of it.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy