Eight years ago, news outlets roundly declared that the Great Recession killed the Las Vegas dream, or at least mauled it.

They described swaths of darkness in the Strip’s sea of lights, with unemployment and foreclosure rippling from an epicenter of stalled construction. Gaming and tourism took heavy losses as budgets tightened. The boomtown busted, and the state with it.

Since then, the same voices have crowed about vibrant turnarounds or warned of hollow comebacks. Many see a mix of slow growth and risks that exist no matter what we’ve learned from the past or how much we analyze the present. Just as the roots of the downturn can’t be summed up in a few statistics, neither can the substance of the recovery. Yet the numbers keep skewing positive, tempting hope that feels dangerous.

The situation looks much better on the surface, but some analysts worry about an unexpected event triggering a new recession. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen remains optimistic. In late June, Yellen said she did not believe the U.S. would see another financial crisis “in our lifetimes.” She applauded regulatory moves that reined in banks, though those measures face potential threats in Congress.

Nevadans want to trust Yellen’s message and the momentum they see in their own communities, but are we really on the right track? We dug into several pillars of the state’s economic outlook, connecting some dots for a clearer picture of where we stand.

REAL ESTATE

Home buying, then and now

“It’s all about accountability. Prior to the recession, you could get away with just having a great credit score and be qualified to purchase anything. There were looser requirements across the board from money down to creditworthiness. Now, it’s as honest as I’ve seen it. You literally have to be able to produce what you say you make, how much money you have in the bank — they follow up on everything. ... I believe the stricter requirements have kept our market under control, because if anyone can get a loan, we would see what we saw 10 years ago, where you and I are talking about the five houses we both bought because we’re speculating. (Now) people just want a home for themselves.”

— Dave Tina, Greater Las Vegas Association of Realtors president and owner/broker of Urban Nest Realty

Despite the unprecedented crash of the Southern Nevada housing market during the recession, steady economic recovery has spread through the region in the current decade, evidenced by seven consecutive years of rising housing prices. This year’s sudden sharp increase, however, invites questions of whether another housing bubble could grow within the local market.

While most experts see more sustainable conditions now than before the recession, the dwindling supply of new and resale homes in Southern Nevada offers some pause.

“Overall availability is now tracking at just over one month of inventory. This market dynamic is pushing price points north as multiple buyers are seeking a shrinking pool of homes, particularly at the lower end of the pricing spectrum,” Applied Analysis Principal Brian Gordon said. “With multiple offers, those financing acquisitions with loans are getting squeezed out by cash buyers in many instances.”

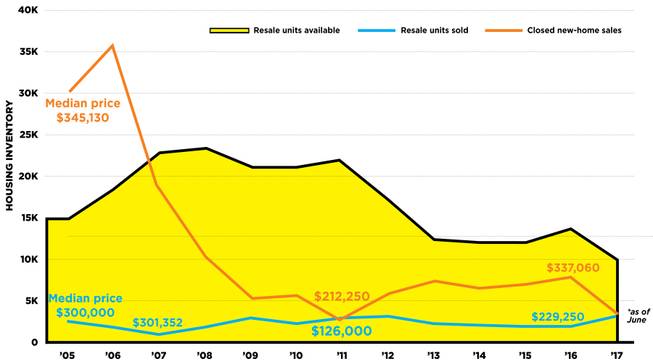

Existing home inventory is at a historic low

Southern Nevada’s resale housing supply in 2017 fell to depths not seen since before the recession. At that time, new-home construction boomed, offering potential buyers both options. Notice, though, that far fewer new-home sales closed in the past 18 months than during the pre-recession period — builders are not producing houses anywhere close to the rate they did years ago. With fewer homes available and more buyers jumping back into the market with rebuilt credit, soaring demand drives prices upward.

• Foreclosure then: Nevada’s foreclosure rate topped the country for more than five years, finally receding in the spring of 2012. It peaked around 10 percent in 2009, meaning 1 in every 10 homes received a foreclosure filing. For a sense of how severe that is, consider that foreclosure monitor RealtyTrac starts the “high” classification at 1 in every 494 homes.

• Foreclosure now: The rate of Nevada homes with a foreclosure filing today, according to RealtyTrac, is 1 in every 1,095, with 26.6 percent up for auction, 34.4 percent bank-owned and 39 percent in pre-foreclosure. Distressed mortgages tend to be more prevalent in rural counties, though Clark County is No. 4 in the state for the most foreclosure actions.

UNEMPLOYMENT

Nevada per capita personal income before and after the recession

• 2006: $39,930, No. 15 in the U.S.

• 2016: $43,637, No. 34 in the U.S.

Unemployment in the West

• Nevada: 13.7% peak; 4.7% as of May

• Colorado: 8.9% peak; 2.3% as of May

• Idaho: 9.7% peak; 3.2% as of May

• Utah: 8% peak; 3.2% as of May

• Oregon: 11.9% peak; 3.6% as of May

• Montana: 7.4% peak; 3.9% as of May

• Wyoming: 7.2% peak; 4.1% as of May

• Washington: 10.4% peak; 4.5% as of May

• California: 12.2% peak; 4.7% as of May

• Arizona: 11.2% peak; 5.1% as of May

• New Mexico: 8.3% peak; 6.6% as of May

When the recession hit the West, no other state’s employment figure tanked harder than Nevada’s. In 2010, the jobless rate hit bottom at 13.7 percent. Nevada was, according to its Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation, “the hardest-hit state during the Great Recession, with employment impacts arriving later and lingering longer than in the U.S. as a whole.”

Today, the unemployment rate is 4.7 percent, the lowest point since before the downturn. State economists and academics agree there’s room for improvement, but given the context, they say Nevada’s economic health has turned around significantly.

Many of the jobs disappeared from the construction industry. Those jobs are coming back with big pending projects like the off-Strip stadium that will house the Raiders, and other sectors have seen modest gains.

A full recovery to pre-recession levels, though, doesn’t mean we’re operating at full strength. In 2015, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released a report on labor underutilization, also known as “underemployment.” This term includes people who involuntarily work part time because of bad business conditions or who want to work but have given up looking for opportunities, which some experts think is a more accurate metric than unemployment. BLS data showed that Nevada led the nation for underemployment that year, at 13.9 percent of the labor force. In 2016, it was slightly better, 12.2 percent, though still significantly higher than the national average of 9.6 percent. Within that figure, 73,300 Nevadans were employed part-time because of economic constraints, and 17,700 had given up despite past efforts to get jobs.

While employment has recovered, engagement in the labor force has decreased across the U.S. since the recession, and at a faster rate in Nevada than the national average. What’s driving this trend is hard to pin down, but it’s possible that an aging population is contributing. As more baby boomers retire, the labor pool shrinks, but they still count as not participating in the labor force. Migration to Nevada might plays a role, as the state draws many who don’t necessarily have jobs and plan to get one.

OUTPUT

Top 5 Nevada industries by GDP

• 20%: Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing

• 17%: Arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation and food services

• 11%: Government

• 11%: Professional and business services

• 7%: Retail trade

Nevada GDP by year

• 2005: $135 billion

• 2006: $138.6 billion

• 2007: $138.5 billion

• 2008: $126.8 billion

• 2009: $119 billion

• 2010: $121.9 billion

• 2011: $121 billion

• 2012: $117.7 billion

• 2013: $120.9 billion

• 2014: $123.2 billion

• 2015: $127.2 billion

• 2016: $131.1 billion

Gross domestic product, or GDP, is how governments gauge the prosperity of their jurisdictions. The New York Times once called it “a figure that compresses the immensity of a national economy into a single data point.” That compression receives plenty of criticism as a measure for overall economic health. Still, GDP remains a key indicator, and Nevada is one of five states that hasn’t recovered to pre-recession levels (the country as a whole reached the milestone in 2012). The other states are Wyoming, Arizona, Mississippi and Connecticut, all experiencing slower bounce-backs.

In 2006, Nevada’s GDP in current dollars was $128.3 billion, good for a national rank of 30th. In 2016, it was No. 33 with a total of $147.5 billion in current dollars. How could the value of current-dollar GDP increase and the ranking go down? Inflation. When adjusted, Nevada’s GDP has not recovered to pre-recession levels. It has steadily improved, but at the end of 2016, the adjusted GDP was $131.1 billion, down from $138.6 billion at the end of 2006.

The gig economy is growing without hurting payrolls: A Brookings Institution report from October showed an increase in “gig employment,” or the use of contractors or freelancers, following a trend established in the 1990s. With the rise of Airbnb and Uber, the report specifically looked at the hospitality and transportation sectors. It concluded that payroll employment in the U.S. continued to grow, despite the increase in gig employment. What that means is hospitality and transportation companies continued to add employees to the payroll, even as the use of independent contractors increased.

The report showed that between 2012 and 2014 in Nevada, gig employment in transportation grew by about 105 percent, or 880 Nevadans, while payroll employment grew by 4.4 percent, or about 550 workers. In the business of traveler accommodations, gig employment grew by 17.7 percent, or 44 Nevadans, and payroll employment gained 3.5 percent, or 5,758 workers.

The health care sector unrattled: Not a single net health care job was lost in one of the states hit hardest by the recession, according to Brookings Mountain West’s Robert Lang, and growth in that area was the top priority for Southern Nevada laid out in a plan for the Governor’s Office of Economic Development. “Las Vegas is just big enough to need a lot of health service, and it’s only doing about two-thirds (of the demand),” Lang said.

The valley has many irons in the fire in this sector, such as four Dignity Health-St. Rose Dominican hospitals slated to open this year, Southern Hills Hospital’s new family medicine residency program, UNLV’s new medical school and the capital campaign by Roseman University of Health Sciences to launch its own school of medicine in 2019, and the 170-acre health care complex Union Village slowly coming together in Henderson.

Still, health services typically account for 18 percent of a regional economy, Lang said. But medicine makes up about $12 billion of Southern Nevada’s $100 billion economy. Lang says building up the quality and density of providers should help, as some people forgo care here or seek it in LA or Phoenix.

THE STRIP AND BEYOND

Visitation on the Strip

• 2007: 39,196,761

• 2009: 36,351,469

• 2016: 42,936,109

Considering the central amplifying effect of the Strip on the economy, the facts that only one new casino has been built in the past seven years and gaming revenue still lags behind pre-recession peaks suggest Las Vegas isn’t what it used to be. That might be a good thing. While the Strip hasn’t yet broken its own records, it isn’t weaker, just different.

• Construction: Between 1993 and 1999, the Strip added nine new resorts and, even as the recession progressed, Wynn, Encore, CityCenter and the Cosmopolitan all came online. Since then, construction of new resorts on the Strip (the Lucky Dragon is technically not within the boundary) essentially stopped. But companies haven’t stopped expanding and renovating, from adding new features like T-Mobile Arena, the Park, and the High Roller to transforming the Imperial Palace into the Linq and the Barbary Coast into the Cromwell, with the Monte Carlo in the midst of becoming two separate hotels.

• Visitation: More people than ever are coming to Las Vegas. The Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority reported 42.9 million visitors in 2016, surpassing 2007’s peak of 39.1 million. The number of convention visitors also exceeded pre-recession levels, but tourists aren’t behaving the way they used to. “The growth we have seen in gaming revenue has been slow, especially when you compare gaming win growth to rooms, food and beverage and other revenue areas, which are all at all-time records,” said Michael Lawton, senior research analyst with the Tax and License Division of Nevada’s Gaming Control Board. “On the positive side, record numbers of visitors are coming, spending record amounts of money. It just so happens that they are spending differently.”

• Revenue: Gross gaming revenue (GGR), yearly hotel occupancy and revenue per available room (RevPAR) in Las Vegas have only recently approached pre-recession levels. In 2007, GGR was nearly $11 billion and occupancy was 90.4 percent, and in 2006, RevPAR reached almost $150. According to 2016 data from the LVCVA, GGR topped out at $9.8 billion and, according to numbers released several weeks ago, year-to-date occupancy was at 89 percent and RevPAR just over $119.

DIVERSIFICATION

In 2012, the Governor’s Office of Economic Development rolled out a plan for diversifying the state’s economy.

“They never got past gaming in Atlantic City,” says UNLV Greenspun College of Urban Affairs professor Robert Lang, who has championed diversification of Nevada’s core. Lang is director of Brookings Mountain West, which wrote the report for GOED. While the state continues to rely on traditional sectors, he said it was developing others to fall back on.

The state is looking to grow its economy through industries including health care, clean energy, aerospace and information technology, in the midst of the new recreational marijuana market making its mark with millions in sales in its first few days.

“If the U.S. economy went into a tailspin and you cut down on consumer spending, you’d see it immediately in the state,” Lang said. “It’s not diversified past the reliance on tourism and on consumer spending, but it’s getting better. It’s getting more robust, and it’s getting more complex. It’s adding new features and new functions.”

ENERGY

Renewable energy is a focus for GOED, and with the Legislature’s recent decision to revamp the system for crediting rooftop solar customers for excess energy, companies have announced that they will restart operations in the state chilled by previous anti-solar decisions. Lang said the solar industry had been booming and rich in jobs before a December 2015 Public Utilities Commission decision gutted the net metering program that reimbursed customers for excess energy generated. Proponents say the new law will boost the state’s renewable energy industry and add jobs.

“This was a really good session for the solar industry,” Lang said.

Renewable energy is like the health industry in that it’s an area where growth stands to increase the state’s independence, Lang said. Nevada has no coal and very little gas and oil development, so he said the state imports whatever energy it cannot provide in much the same way that a lack of health services pushes patients out of state.

TECHNOLOGY

In Northern Nevada, Lang said, the focus shifted from tourism to technology. Even with Tesla, an electric car and battery company with a factory and warehouse there, Lang said the state was still not a technology powerhouse, though it’s making progress.

In the south, Faraday Future’s announcement that it would halt plans for a primary vehicle production plant highlights the volatile nature of Nevada’s push to attract business with tax incentives.

Meanwhile, Apple recently announced plans for $1 billion of expansion in and near Reno after receiving an $89 million tax package years ago. Nevada also continues to be a national leader in testing of autonomous vehicles and unmanned aerial devices. Both of those are focus areas of GOED’s diversification plans.

MARIJUANA

Starting July 1, the new industry made $3 million in sales through the first four days of legal recreational marijuana, according to the Nevada Dispensary Association. That’s $750,000 per day, and about $125,000 in state taxes (which would have been higher had the coming 15 percent wholesale distribution tax been applied).

While kinks in the new system need to be worked out — there are problems with supply and distribution, in addition to confusion about company and consumer compliance with regulations and laws — the industry is likely to follow in the footsteps of successful models in Oregon and Colorado. It is projected to generate about $500 million in sales over the next two years, kicking in $110 million in tax revenue to the state’s rainy day fund. And by 2020, it is expected to create 3,298 direct full-time jobs.

Growth also is anticipated in the state’s fledgling hemp industry now that lawmakers have approved retail sales of the crop.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy