A giant step backward. A declaration of war. The worst legislation for women’s health in a generation.

These were among reactions to the May 4 passage of the American Health Care Act through the U.S. House of Representatives, from the American Civil Liberties Union, advocacy group UltraViolet and health care provider Planned Parenthood, which would lose all federal grants and reimbursements for a year if the bill were to clear the Senate.

“This disastrous legislation once again makes being a woman a pre-existing condition,” Planned Parenthood President Cecile Richards said in a news release, referring to the Republican bill’s callback to an era when insurers could treat pregnancy, C-sections, postpartum depression, domestic violence and sexual assault as pre-existing conditions, charging affected women more or denying coverage. The AHCA would allow states to opt out of the Affordable Care Act’s provision for pre-existing conditions, and it would block private plans from covering abortion and limit options for low-income women on Medicaid.

The GOP’s website asserts that “praise has poured in” for the party’s plan, rounding up op-eds from Forbes, Fortune, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and some smaller outlets, as well as statements from the National Federation of Independent Business and other trade groups, mostly lauding fiscal aspects such as cutting industry taxes and lifting regulations imposed by the Affordable Care Act. Polls show some support for its intended replacement, though a majority stands in opposition. Quinnipiac University Polling revealed that out of more than 1,000 Americans surveyed, only 22 percent of men and 13 percent of women were in favor of “Trumpcare.” Nearly a quarter of respondents who identified as Republicans were not among them.

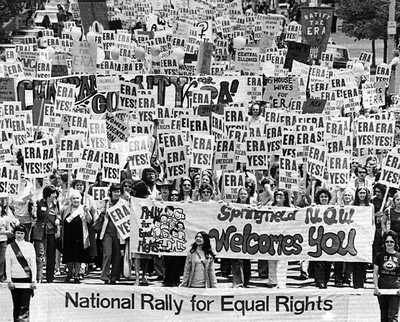

The group that organized the Women’s March on Washington the day after President Donald Trump was inaugurated, which inspired millions to demonstrate across the world for social justice, called for May 8 to be the final phase of its “10 Actions in 100 Days” campaign. According to Bustle, organizers already had nonviolent demonstrations planned. “Then the House of Representatives pushed through a bill to gut health care in a short, less-than-24-hour window. They wanted to avoid the time for resistance to build. But they actually created momentum around resistance because health care affects every single one of us," Women’s March head of communications Cassady Fendlay told Bustle. Women and men again took to the streets to raise their voices and handmade signs with such messages as “Accessible doesn’t mean affordable” and “Nevertheless, I pre-existed.”

At the January march, the Jezebel blog snapped a photo of a black man carrying a sign that read: “Women’s Rights are Human Rights.” Asked how he felt threatened by a Trump presidency, he said: “I don’t know if I feel personally threatened, but it’s revealing a lot of truths about the country that people might not have wanted to recognize.”

In the wake of second-wave feminism’s work from the 1960s through the 1980s, American girls grew up with what Joanne Goodwin calls at least the perception of equality. The UNLV history professor has directed the Women’s Research Institute of Nevada for almost 20 years, and anecdotally has seen positive sea changes manifest on campus, from the number of Latina students running with educational opportunities to the men accounting for as much as 40 percent of her class on women’s history. Even so, she reminds that “once a law passes, it’s not there forever.” Ground gained isn’t necessarily solid.

And the group carrying the banner has always been small, Goodwin says, whether you go back a century or look at political engagement beyond the occasional march in a hand-knit pussy hat. But Trump’s administration has shaken the perception of where women stand. More and more people are examining the reality.

“Better woke now than never,” Goodwin says.

WHERE NEVADA RANKS

The Status of Women in the States is an ongoing national data project of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, a think tank launched in 1987 to analyze public policy through the lens of gender. “Women in Nevada have made considerable advances in recent years but still face inequities that often prevent them from reaching their full potential,” IWPR reported in 2015.

Here's how states in the West ranked nationwide for opportunities and support for women:

Shifting tides for millennials

Though millennial women face some of the same challenges as older generations, the tides may be turning. According to a 2015 report from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, of all those ages 16-34 in 2013, 34.2% of women work in managerial/professional occupations compared with 25.4% of men. Millennial women 25 and older also are much more likely than their male counterparts to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher — 36.3% compared with 28.3%. This is a considerable departure from higher education rates among all women and men, which are 29.7% and 29.5%, respectively. While millennials still contend with a gender wage gap, it is slimmer than the overall ratio of 85.7 percent for full-time, year-round workers. With continued forward progress and a dedication to empowering young women across the state, Nevada could be one of the first in the nation to close the wage gap — promoting economic growth and professional equality between genders.

Political participation Grade is a composite index based on these indicators: voter registration and turnout, representation in elected office and an index of women’s institutional resources.

Nevada: D-, #42; Washington: B, #4; Oregon: B-, #6; California: C+, #8; Idaho: D-, #40; Utah: F, #50; Arizona: C, #14; Montana: C, #10; Wyoming: D, #34; Colorado: C-, #19; New Mexico: C-, #23

Employment and earnings Grade is a composite index based on these indicators: median annual earnings of women who work full-time/year-round, gender-based earnings ratio among full-time/year-round workers, women’s labor force participation and the percent of employed women in managerial or professional occupations.

Nevada: D, #41; Washington: B-, #17; Oregon: C+, #20; California: B-, #15; Idaho: F, #50; Utah: D, #39; Arizona: C-, #34; Montana: D-, #45; Wyoming: C, #28; Colorado: B, #12; New Mexico: C-, #31

Work and family Grade is a composite index based on four indicators. Three relate to work-family policy: paid leave, dependent and elder care, and child care. The fourth is the gender gap in labor force participation of parents of children younger than 6.

Nevada: C-, #23; Washington: C+, #14; Oregon: B-, #6; California: B, #2; Idaho: D-, #46; Utah: F, #50; Arizona: D, #38; Montana: F, #49; Wyoming: D-, #47; Colorado: C+, #11; New Mexico: C-, #27

Poverty and opportunity Grade is a composite index based on these indicators of women’s economic security and access to opportunity: health insurance coverage, college education, business ownership and poverty rate.

Nevada: D, #39; Washington: C+, #15; Oregon: C, #25; California: C, #23; Idaho: D, #43; Utah: C-, #29; Arizona: D+, #35; Montana: D, #36; Wyoming: C, #23; Colorado: B-, #8; New Mexico: D, #43

Reproductive rights Grade is a composite index based on these indicators: mandatory parental consent or notification laws for minors receiving abortions, waiting periods for abortions, restricting public funding for abortions, percent of women in counties with at least one abortion provider, pro-choice governors or legislatures, Medicaid expansions or state Medicaid family planning eligibility expansions, coverage of infertility treatments, same-sex marriage or second-parent adoption for individuals in a same-sex relationship, and mandatory sex education.

Nevada: B, #17; Washington: B+, #10; Oregon: A-, #1; California: B+, #9; Idaho: F, #48; Utah: C-, #37; Arizona: C+, #24; Montana: B+, #11; Wyoming: C-, #35; Colorado: C+, #21; New Mexico: B+, #12

Health and well-being Grade is a composite index based on these indicators: mortality rates from heart disease, breast cancer and lung cancer, incidence of diabetes, chlamydia and AIDS, average number of days per month that mental health was not good or activities were limited due to health status, and suicide mortality rates.

Nevada: D, #40; Washington: C+, #14; Oregon: C, #24; California: C+, #17; Idaho: C+, #14; Utah: B, #4; Arizona: C-, #28; Montana: C, #25; Wyoming: C+, #20; Colorado: B, #6; New Mexico: D+, #33

THE GENDER PAY GAP

The Equal Pay Act was signed into law in 1963 by President John F. Kennedy, mandating that men and women receive equal pay for “substantially equal” work. A year later, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act to protect against discrimination based on national origin, race, religion or gender. Regardless, disparity remains. Nationally, men earn an average of $51,212 annually, and women earn $40,742 — only 80 percent. And women of color face larger gaps. Compared with white men, black women are paid 60 cents on the dollar and Latinas are paid 55 cents on the dollar. In Nevada, black women are paid 65 cents on the dollar, Latinas are paid 52 cents on the dollar and Asian women are paid 68 cents on the dollar.

Positives and negatives

IWPR finds that on average, women in Nevada who are unionized earn $125 more per week. According to the National Women's Law Center, American mothers working full-time earn less than fathers working full-time: 71 cents to the dollar. It’s even worse for single mothers, who make 55 cents to the dollar.

The U.S. Joint Economic Committee’s Democratic staff last spring released a report called “Gender Pay Inequality: Consequences for Women, Families and the Economy.” Key takeaways included the assertion that while economists believe complex factors cause the pay gap — occupational and industry differences, levels of experience and education, unionization — as much as 40 percent of the disparity may be attributed to discrimination. The report also found that the pay gap can add up to almost $11,000 a year. In Nevada, it’s $6,301, according to 2015 data from the U.S. Census Bureau, amounting to a combined total loss each year of about $2.4 billion.

While the gap has narrowed, the rate of change indicates it won’t close nationally until 2059, according to the IWPR. Based on the rate of progress between 1959 and 2013, Nevada women could see equal pay sooner, by 2044. The National Partnership for Women and Families estimates that if the pay gap were eliminated in Nevada, one woman could afford: almost 7 more months of rent, 5 more months of mortgage and utility payments or 46 more weeks of food for her family.

Are there protections for women in the workplace?

In an American Association of University Women breakdown of 23 equal pay laws, Nevada was listed as having moderate protections, as all or most employees have the benefit of equal pay or employment discrimination law; no retaliation/discrimination for involvement in related legal proceedings; and no reductions in other employees’ pay to reach compliance. States with strong protections include California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, Minnesota and Vermont. Alabama and Mississippi have no equal pay protections.

Here’s a look at median average earnings across the Western states in 2015:

Nevada, #11 Men: $43,681 / Women:$36,565

Washington, #25 Men: $56,215 / Women: $44,422

Oregon, #21 Men: $48,001 / Women: $38,774

California, #7 Men: $50,562 / Women: $43,335

Idaho, #44 Men: $43,264 / Women: $31,808

Utah, #48 Men: $50,741 / Women: $36,060

Arizona, #13 Men: $44,421 / Women: $37,084

Montana, #46 Men: $46,123 / Women: $33,443

Wyoming, #51 Men: $55,965 / Women: $36,064

Colorado, #22 Men: $51,628 / Women: $41,690

New Mexico, #8 Men: $41,440 / Women: $35,070

EMPLOYMENT SNAPSHOT

According to 2014 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 1,288,000 employed people in Nevada that year. Of those, 712,000 were men and 576,000 were women: 30.5% of those women were in the service industry; 19.9% in professional fields; 19.3% in office and administrative support; 12.6% in management, business and finance; 12% in sales; 2.1% in transportation and material moving; 0.6% in construction and extraction; 2.4% in production; 0.4% in installation, maintenance and repair; 0.1% in farming, fishing and forestry.

IWPR's 2015 report ranked Nevada 16th in the nation for the number of women-owned businesses, as it's close to 30 percent. But in terms of female workers in managerial/professional positions, a similar percentage landed the state dead last.

POLITICAL SNAPSHOT

The Center for American Progress estimates that at the current rate, American women won’t reach parity with men in terms of representation in leadership until 2085. While they represent more than half the nation’s population, they don’t come close to that in terms of women holding seats in state legislatures or in Congress.

• Women hold close to 40 percent of the seats in the 2017 Nevada Legislature: Of 42 Assembly members, 17 are women. Of 21 senators, eight are women.

• In 2012, 56.2% of Nevada women were registered to vote (national rank, 49), and 45.4% made it to the polls (national rank, 46).

EDUCATION SNAPSHOT

Overall in the U.S.

Educational attainment by women has improved substantially and at a faster rate than men since 1990. That year, according to U.S. Department of Commerce data, about 23% of men 25 and older held at least a bachelor’s degree, while about 17% of women did. Now, more than 30% of both groups have reached that level. However, the U.S. Joint Economic Committee's report found that a typical woman with a graduate degree annually earns $5,000 less than a typical man with a bachelor’s degree.

Education is one area in Nevada in which all demographics are affected by a broken system. Education Week’s 2017 Quality Counts report ranked it 51st among the 50 states and the District of Columbia, with an overall grade of D for poor performance in K-12 achievement, school finance and chance for success.

Given how crucial STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education is to Nevada’s economic development strategy, there is some focus on increasing female participation in school, exemplified by the Northern Nevada Girls Math and Technology Program, offered since 1998 through UNR’s College of Education. "Research indicates there is a middle school drop, where girls start opting out of STEM disciplines,” program director Lynda Wiest said in a 2015 post on UNR’s website. “This program targets students before that gap to increase interest and make sure these students don’t make a choice to drop out of something they may, in fact, be interested in and good at.”

U.S. Census data from 2015 suggests such efforts have made a difference nationwide, as women represent 63 percent of all social scientists, 47 percent of life scientists, 45 percent of mathematicians/statisticians and 14 percent of engineers.

When it comes to higher education, Nevada women are on par with men, just over 22 percent of both groups holding a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to a 2015 report from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Nationally, that's only good for 48th place.

UNLV is known for its diverse student body, and this year it is majority female, with 16,931 women to 12,771 men. Here is where women are concentrated across the colleges: Liberal Arts: 2,267 students (65% of total); Urban Affairs: 2,033 students (66% of total); Education: 1,989 students (78% of total); Sciences: 1,696 students (56% of total); Business: 1,662 students (45% of total); Hotel Administration: 1,420 students (60% of total); Nursing: 1,279 students (78% of total); Allied Health Sciences: 1,269 students (59% of total); Fine Arts: 1,138 (55% of total); Engineering: 480 (18% of total); Community Health Sciences: 332 students (75% of total); Law: 183 students (47% of total); Dental Medicine: 148 students (43% of total)

*Of the 60-member charter class of the UNLV School of Medicine, 31 are women.

HEALTH SNAPSHOT

The Legislative Council Bureau's 2015 fact sheet compared residents' physical health and health care options to national averages. Here are some key findings for the overall population:

• Per capita state and local government expenditures for health programs, 2012: National, $269 / Nevada, $132 = 49th

• Percent of state and local government expenditures used for health programs, 2012: National, 3.3 / Nevada, 2 = 41st

• Percent of population not covered by health insurance, 2014: National, 10 / Nevada, 13 = 6th

• Estimated per capita Medicaid expenditures, 2014: National, $1,444 / Nevada, $812 = 49th

• Percent change in state Medicaid expenditures, 2013-2014: National, 11.3 / Nevada, 14.1 = 15th

• Rate of physicians per 100,000 population, 2013: National, 326 / Nevada, 226 = 47th

• Rate of primary care physicians per 100,000 population, 2013: National, 100 / Nevada, 71 = 49th

• Percent of adults who participate in weekly aerobic physical activity, 2013: National, 50.8 / Nevada, 53.6 = 17th

• Percent of adults who smoke, 2013: National, 19 / Nevada, 19.4 = 24th

• Percent of adults overweight, 2013: National, 35.4 / Nevada, 38.6 = 1st

Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention drills down to women's stats, showing that the state does not have robust offerings in terms of reproductive health services.

Poverty, which can contribute to conditions that affect a woman's mental and physical condition, afflicts 26% of the 128,000 or so households in Nevada headed by women.

The number of incarcerated women is rising in Nevada with nonviolent crimes. The Nevada Department of Corrections reports that 1,372 female inmates represent almost 10 percent of the state’s prison population and that women are the fastest-growing inmate demographic. In a 2015 story from UNLV’s news center, criminal justice professor Emily Salisbury pointed to economic stress and addiction as major drivers of female infractions. Because many incarcerated women struggle with histories of substance abuse, mental health issues and unhealthy relationships — Salisbury says 77-90 percent report some form of abuse in their pasts — they have that much more trouble rehabilitating their lives. But she said Nevada was “making some serious strides to implement best practices for the female population,” including working with her on getting grants to fund research and new support and training programs.

-

Sarah Weddington poses for a photo inside the Westgate Las Vegas on March 30, 2017. She was the lawyer who successfully represented "Jane Roe" in the landmark Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade.

SARAH WEDDINGTON

Before Sarah Weddington was an icon of women's rights in America, she was simply a woman being told she couldn't achieve what she wanted to achieve. Not only did she disregard that and become a lawyer, she made history in successfully representing Norma McCorvey, aka "Jane Roe," in the landmark Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade. Weddington went on to three terms in the Texas House of Representatives and was the first woman to be general counsel of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. From 1978 to 1981, she served as assistant to President Jimmy Carter, directing his administration's work on women's issues. She continues to speak and write for their advancement, urging the young generation to get involved.

Why did you choose to practice law?

My original goal was to teach eighth graders to love “Beowulf.” I tried that, and I thought, there has to be something better that I can do. That’s when I decided that maybe I could practice law. I talked to a lawyer in the church my father was pastor of. He said, “You really ought to think about this because it’s something you can use in many different ways. You will meet a lot of people in law school that you may become lifetime friends with. It’s a way to really have impact.” The more he talked about what he saw was the plus, the more I thought, maybe I’ll do that.

Then I went to the dean of students at the McMurry University in Abilene, Texas. I said, “I think I want to go to law school.” He said, “No, you can’t. No woman in this college has ever gone to law school. It would be too tough.” That was the moment that I decided that I was going to go to law school. I got accepted in 1964. At that point, there were so few women in law school that if you could get a good score on the admission test, you had a real good chance of being admitted. They needed the diversity.

I went to the University of Texas School of Law. When I got out, I started looking for a job. There was a lot of resistance in the legal profession to having women in it. But eventually I got a job with the city attorney for the City of Fort Worth.

What was your experience in law school?

There were five women in my class. Now women at the University of Texas Law School make up half of the school. It has really changed.

What was it like working for the city attorney in Fort Worth?

The city attorney was named S.G. Johndroe Jr. He would sit in his office and yell for me. I would go in there and tell him, “Johndroe, I wish you would call me on the telephone.” He would say, “Well, I thought you’d want me to treat you just like everybody else.” He did yell for the men as well.

How did you become involved in this landmark case?

There was a group of women who were graduate students at the University of Texas. The main one was Judy Smith. Judy said to me one day, “The University of Texas Health Center won’t tell anybody about contraception.” Students had no access to contraception or information about contraception. Judy and a group of volunteers started a counseling effort. They had a little area where they would provide information about contraception. A number of women came forward who were already pregnant and asked, “Where can I get an abortion?” Judy and the volunteers started traveling to see where pregnant women could go. At that time, abortion was partially legal in California, Colorado and New York. Those were places they could refer women to. But of course, for women to take advantage of that, they had to have the money for the plane, somewhere to stay, the procedure itself. You had to have a good deal of money.

I knew Judy from a women’s liberation group. Judy told me, “We feel like we might be prosecuted as accomplices (to women getting abortions).” Back then, abortion was only legal to save the life of the woman. Nobody knew what that meant. The doctors would basically not do procedures.

Will pro-choice abortion rights remain in place?

Americans have mulled that question since the February 2016 death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and the April 7 confirmation of conservative federal Judge Neil Gorsuch. Gorsuch restored ideological balance to the court, but Democrats worry the next Supreme Court appointment might empower those who hope to overturn Roe v. Wade and end legal abortions. While that’s unlikely, here’s a look at the legislative machinery:

State level: State governments create and pass laws of their choosing, so one could vote to ban abortion at all stages of pregnancy. However, that’s unlikely because a lawsuit would almost certainly be filed, and the state law would be struck down as unconstitutional under Roe v. Wade.

Federal level: The Supreme Court cannot revisit a case on its own. Justices can only hear a case that challenges a past ruling if it is brought before the court and they agree to hear the arguments. If the justices agree to hear one, overturning a ruling like Roe v. Wade would require a majority to be in favor of striking down the previous decision.

Judy one day said to me, “We are concerned about our own legal standing. We think we should have a case that would test Texas law and if the law is overturned, then we know where to send women.”

There was a hospital called Parkland Hospital that had a ward called the Infected Obstetrics Ward, where the women who had done self-abortions or who had had an abortion and ended up having all kinds of problems were. The doctors often had experience trying to save women’s fertility and trying to save their lives. I think that was one reason why the medical association in Texas was very supportive when I was working on Roe v. Wade. They knew that if abortion was illegal, it didn’t mean there would be no abortion. It meant abortion would be a lot more dangerous.

Judy said to me, “What would you charge us to do this case?” I said that I really thought it would be better if she got a lawyer who was more experienced. I had never done a case in federal court. … (After doing some research), I told Judy that I would work on the case for free. She said, “You are our lawyer.”

What was the process in getting Roe v. Wade to the Supreme Court?

First the case went through a three-judge federal court in Dallas. That court ruled that the law was unconstitutional. But we had asked for an injunction against Henry Wade, who was the district attorney of Dallas. We asked that he be told that he could no longer prosecute doctors who performed abortions. He then had a press conference and said he didn’t care what any federal court said. He would continue to prosecute.

There’s a procedural policy in law that says if a three-judge court rules that they would not give an injunction because they believe a locally elected official would abide by the judgment of a three-judge federal court, then you have a straight appeal to the Supreme Court. … The Supreme Court can decide whether to take a case.

We got notice that the court decided to take the case. That was at a time when all the justices of the Supreme Court were men. We went up to argue our case and the day we argued, it was informally called “Women’s Day” at the Supreme Court because there were two cases argued that morning. There was my case and there was a Georgia case on abortion. That case involved a Georgia law that said that abortion was illegal except in the case of rape, incest, fetal deformity and to save the life and health of the woman. The plaintiff side was being argued by a woman. And the attorney general in Georgia sent a woman lawyer. So there were four people who were arguing that day and three were women.

What was it like putting together your argument? What were you thinking? What were you feeling?

I felt that it was a responsibility. I knew there were women who were pregnant who didn’t want to be. I thought that I had to do whatever I could legally to try to be sure women could make the choice and not the government.

Did you believe there was a chance you could win even though the Supreme Court was made up of all male justices?

I thought we had a chance because in 1965 there had been a case called Griswold v. Connecticut. Connecticut had a law that said even married people couldn’t have access to contraception. A woman who was the head of Planned Parenthood in New Haven, Connecticut, named Estelle Griswold and a doctor named Lee Buxton had given a married couple a contraceptive. They were arrested, prosecuted and convicted as accomplices to the use of a contraceptive device. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that it was up to the couple whether to use a contraceptive. It was not the government’s decision. The court talked about the right to privacy. I thought that given the decision in that case that we had a chance to win.

Describe what happened after the Supreme Court ruled in your favor.

I knew a doctor in Austin who had a patient who was getting ready to leave for California later that day to have an abortion. The doctor was able to tell her that she didn’t have to go to California. It was like lightning. The case made the decision and the impact was immediate. There were doctors who had the equipment to perform an abortion because they weren’t afraid of being prosecuted.

Did you ever consider yourself a hero for women?

I think people do what they can. That was something that I was willing to try to do. It never occurred to me that 46 years later that I would still be talking about it.

How should younger people get involved in issues of reproductive rights?

First, Congress and state legislatures can’t make abortion illegal right now but they certainly can pass things to make having an abortion difficult. Young people can elect people who are pro-choice and stop laws that could make having abortions unavailable. Trying to help in those ways is really important.

Is it your mission today to spread that message?

I do a lot of speeches on college campuses trying to talk about why we need cooperation from younger people. There are a lot of younger women in particular who are becoming very active. If you look at the marches that were held not long ago, in most places they had plenty of people participating.

At the march in Austin, there were women wearing T-shirts that said, “Pussies grab back.” I thought that was great fun.

How do you feel about the fact that abortion is still so politically charged and that there are states still trying to make having the procedure difficult?

I’m not going to try to change one person’s mind unless they’re a state legislator. But I would talk to a person about the time when abortion was illegal. That didn’t stop abortions from happening. It just made it much more difficult, much more expensive and often much more dangerous. There are always going to be people who are in the opposition. That’s why we have to have more people in the pro-choice category and to try to protect Planned Parenthood.

Have you talked with pro-life advocates or sympathized with their point of view?

I can certainly understand that they believe differently than I do. But that’s not a reason why their viewpoint should prevail. I really believe the individual should make the decision.

People ask me if the Supreme Court will overturn Roe. I guess I’m an optimist. I still don’t think so right now. But Ruth Bader Ginsburg is 83, so what will happen when someone fills her position? A couple of the men are in their 70s. If the current president will be able to change several of the justices, then it will make me more anxious.

What keeps you going?

What stiffens the spine is opposition.

– Julie-Ann Formoso

-

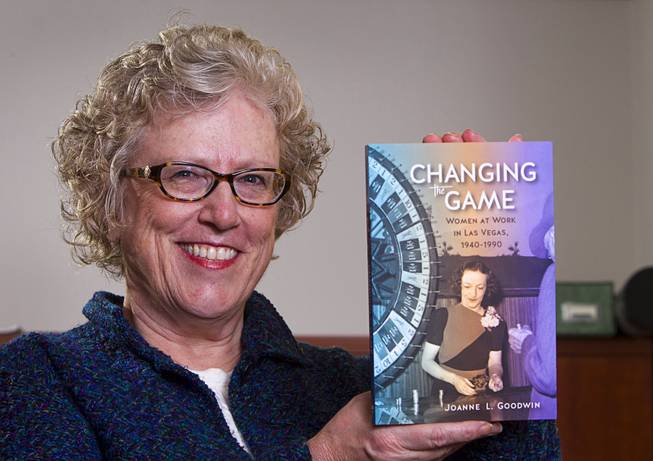

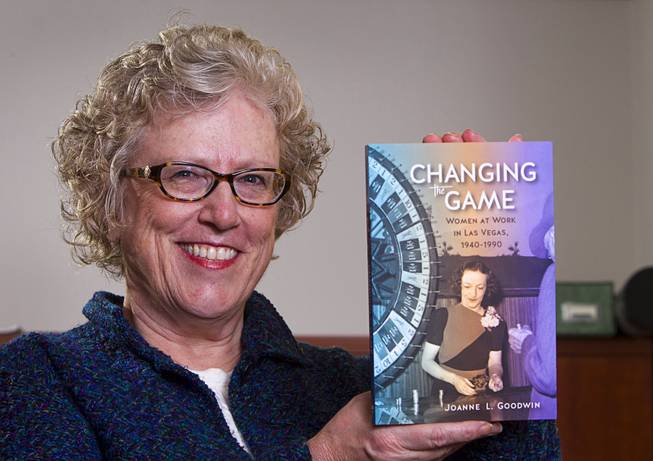

Joanne Goodwin, a UNLV history professor and director of the Women's Research Institute, poses with her book "Changing the Game: Women at Work in Las Vegas 1940-1990" at UNLV Monday, Jan. 12, 2015.

JOANNE GOODWIN

Historian Joanne Goodwin helped create the Nevada Women’s Archive at UNLV, directs the Las Vegas Women Oral History Project and for 18 years has led the efforts of the Women’s Research Institute of Nevada. She’ll step down from WRIN this summer to return to UNLV’s History Department full-time as a professor, having become something of a living encyclopedia of the experience of women in the Silver State.

Nevada women were granted the right to vote in 1914, six years ahead of the country. Why so?

Suffrage became adopted by multiple parties that were at play in Western states — labor parties, socialist parties, farmer/worker parties, the populists — all of those groups recognized the value of collaborating to get political goals accomplished. In older states in the East and the Midwest, the political party system might have been more rigid. So there was a flexibility there politically in terms of structure that enabled women organizing in the West to have an earlier impact.

Did other factors allow some Nevada women to achieve things that were considered exceptional?

I think Nevada’s size has allowed individuals to stand out and accomplish things in a way that wouldn’t have happened even in a larger Western state.

I’m thinking of some women who actually came to Nevada during the mining boom. Bird Wilson is one. … She was a stockbroker, she was an attorney and she even had some mining claims, but we know her in terms of women’s history as the suffrage coordinator for the southern part of the state. … In the north it was Anne Martin. She followed a trajectory that is closer to some other stars of Eastern suffrage in that she got her political training in England with the Pankhursts and what was radical at the time — parades and picketing kinds of activities that were seen as very unfeminine but drew a lot of attention to the cause. So when she came back to the U.S. she aligned with the National Woman’s Party, which was the group that picketed the White House during Wilson’s administration.

So the size, particularly in Southern Nevada — it remained so small in terms of population that women had opportunities that women in older and more formed communities didn’t have. … There’s a rich history here in which some pioneering women all through have broken new ground, some of them working individually but most of them working collaboratively.

… Another pioneer that I really like to promote is Florence McClure, who was a longtime resident of Las Vegas. Florence and her collaborators created (Community Action Against Rape in 1974) to address rape in the greater Las Vegas area. ... She went to Carson City on a number of occasions to change Nevada’s laws about rape, so marital rape was identified and legislation better defined sexual assault as a crime of violence, and to secure assistance in terms of mental health counseling for survivors of rape. People had to do that in communities all across the country in the same way that our domestic violence shelters were created by locals on the ground who saw a need and gained support slowly but surely. ... CAAR’s work extended to education for the police force, education for hospital workers and doctors who saw these women in the ERs. It was just a very slow and very extensive progress that they made, and it has changed the way our community views these issues.

What about the progress made by women of color earlier in the 20th century?

Leadership evolved out of the African-American and the Latina community even though the issues were really quite different. The civil rights story is a remarkable one. … There were a number of women in the ’40s and ’50s, from Lubertha Johnson to Sarann Knight-Preddy to Alice Key — they were strong, powerful, focused leaders who understood at that particular moment in history the significance of race equality and dedicated their efforts to achieving that locally.

There was a 1971 consent decree that was finally a legal, court-mandated compromise between unions and hotel-casinos to employ African Americans. That created a number of openings. What was interesting for the women in our study is that it didn’t change their job status a whole lot — they might get into the casino, but they were still a cook or a maid or a secretary or, in a few rare cases, in publicity offices. So it took another consent decree a decade later to make that same court-mandated request for opening up that employment to women and those of Hispanic origin. So that’s a very real and lively history here.

Nevada Commission on Women

Assembly Bill 258 would revamp the commission, which launched in 1991 but went dormant for almost 20 years. Gov. Brian Sandoval revived it in 2015 by appointing 10 members to the bipartisan group, which is pushing for the ability to pay consultants with grants (instead of depending on volunteers) to support a range of efforts aimed at advancing equality. The bill is still alive in the Legislature and has a chance to pass before the session ends June 5.

Your book, “Changing the Game: Women at Work in Las Vegas 1940-1990,” takes us farther down the timeline of women’s story here. What defined it?

I made a claim that women in Las Vegas who were in the labor force from 1950 to the end of the century were ahead of the game in terms of what was happening nationally. And I based that on a statistical analysis I did of the Census, which showed women came to Las Vegas to work just like men came to Las Vegas to work. Obviously, women also came to Las Vegas with their families, but there was a higher percentage of women in the labor force here than in the country as a whole from 1950 through that whole period. So that’s pretty significant.

There was a change in society going on at the time. It was the dancers and choreographers and producers who wanted to pursue their professional work, or the educators like Maude Frazier who saw an opportunity in the West and took it, or the service workers who came here because it was better than picking cotton and cleaning white women’s houses, and they had a union that could give them not only a living wage but an opportunity to join the middle class and send their kids to college. They came here, a lot of women came here to work, and I think nationally what we’re seeing now is a decline in the percentage of women in the labor force, so we don’t know what the next 10 years will show. Maybe they’ll stabilize, maybe that generation of the boomers’ daughters who grew up with benefits will make different choices. Maybe they will. It hasn’t played out. But in that way, the Las Vegas labor market has been an opportunity for a lot of workers.

Did that trend continue over the past two decades?

It continued. There are women entering professions like law and medicine here, and the city is bringing in people from all over the country with similar kinds of higher educational backgrounds. What saddens me is that our support for education is still so low in this state. Because that, from my position, is something that has to be in place for people to prosper. Not exclusively, but largely. ... Higher education gives you more control and more opportunity as well as a higher salary.

Despite the early success with suffrage, the Equal Rights Amendment did not pass in Nevada in the 1970s, vexing notable Assemblywomen Sue Wagner and Jean Ford and many of their peers. What did they do?

They were able to pass a pro-choice amendment into the state constitution. You would have to change the constitution to change this particular provision that protects women’s right to choose in the state. It’s the best-kept secret, and in a way they wanted it that way because it was political mobilization through religious institutions that defeated the ERA, according to those who have written about it. So they wanted to at least get part of it through.

You have long been involved in the Nevada Women’s Archives, an initiative launched in the 1990s to collect the personal papers of Nevada women who’ve had an impact. How do you reconcile that desire to document the distinct experiences of women without perpetuating the “otherness” that contributes to struggles for equality?

I think it’s a dilemma of the third-wave generation. Women who came of age in an era where equality was at least perceived to be a thing. Women who were able to do sports in school, get into college without discrimination, get their fellowships if they wanted to go into advanced education, get into law school, get into med school — that was a norm that was won, and those women had a perception of acting equal. So did Maude Frazier (the first female lieutenant governor of Nevada, in 1962). She recognized where the barriers were, but she wasn’t going to let any of that stop her. So, I think that’s a very contemporary dilemma: How do you draw attention to the differences and at the same time move forward as equals? Any social scientist, gender researcher or historian will tell you the history is there, that women were not treated fairly. So the question then becomes, what’s happening right now?

– Erin Ryan

-

NATALIE YOUNG

Chef Natalie Young is preparing to launch her third restaurant in Las Vegas, after the successes of downtown spots Eat and Chow. Crediting their popularity to “just simple, good food,” she has used her platform to launch awareness campaigns for pit bulls and addiction, and to start two organizations: Chow to the Core, an apprenticeship program, and Vegas Women Connect, a “community of women who gather to change the narrative through authentic conversations and dynamic relationships.”

How would you describe your professional journey?

I'm in a dominated male, white profession, especially when I started. Not that that was any sort of a hindrance or a handicap for me, but it was what it was, and it is what it is. So, you have to work three times as hard, you know? … In the kitchen, you hold your weight. You carry your own weight. So was it a challenge? I don't know. Did it make me who I am today? Absolutely.

What is the mission of Chow to the Core?

If I ever get the opportunity to do anything in the community or the world, there are three things that are important to me: kids and dogs, because they don't have a choice, and I feel like in Las Vegas there's not really a space for women, all different kinds of women to join together and network and share their experience.

So, my first thing was the dogs. I do a little rescue thing with the pit bulls, so we'll train them up and then we gift them.

My next thing was the kids. I had Eat, and I was sitting there and I was thinking, I have this beautiful restaurant, what am I supposed to do? … I literally woke up one morning and I go: Kids! It's a perfect little culinary school. … My first (Chow to the Core) class was about how to fill out an application, what you wear to an interview, how you shake someone's hand and look them in the eye. People don't teach those things anymore today, and these kids are already underserved and start at the back of the pack. So I thought, wouldn't it be great to give them a little head start? I also thought, if they work with me two or three years, by the time they get out of high school whatever they decide to do with their life they can always be employable because now they have the experience. ... It's an honor and it's a responsibility.

And Vegas Women Connect?

I thought it would be really cool if we had a gathering of women, all different kinds of women — grandmothers and daughters and sisters and mothers and lawyers and doctors and waitresses and artists, and just get us all in a room and talk about not so much what we do, but who we are, and see if we can connect and help one another.

It's been fantastic. We just have all these interesting, innovative women who share their journey into who they are, a little bit of what they do, but mostly about how they got where they're at. Their struggles, you know?

What struggles have you faced as a woman?

I'm kind of odd in that area. I don’t really look at myself as facing struggles as a woman or a black woman or a gay black woman or anything like that. I look at it as life. I try not to be a victim in my journey on the planet. I change my perspective and look at it as a challenge. I thank God every day for the challenges as opportunities to grow. I really do, it sounds freakin’ cheesy, but that’s how I survive — with a positive attitude. Otherwise, I could sit in a corner and shrivel up and be a victim. I don’t choose to be a victim. I write my own check.

Who were the inspirational women in your life?

My mom, for sure. My mom was just a really good home cook, and a nice human in general, so she was very influential and very kind and loving. … I like Julia Child a lot; I just think she was a master chef and a badass in the kitchen, and she was doing it way before any woman. I mean way ahead, and I remember as a kid watching her. And then Joung Sohn — she's the executive chef at the Eiffel Tower now, and she's a great example of how to be professional in the kitchen without emotion, and not in a bad way by any means. In the kitchen in order to run with the guys you can't break down and cry, you've got to handle your business, and she was a really good example on how to do that. She's still a really good friend today. She's a fantastic chef and a great mentor.

What advice would you give young women?

Find something you love to do and don't worry about money. I think people are so caught up about money. I think we were put on this planet to find whatever our gift is and to share that with the world. Some people make a lot of money doing that and some people don't, but at the end of the day I'm rich no matter how much money I made, even when I was making $9 an hour, I loved to cook.

There's guys that were way ahead of me and that were my bosses, and they're still working for somebody. None of them own three restaurants, none of them are doing what I'm doing or had the opportunities I've had. ... There's no secret to it except hard work, and even after hard work you're not promised. You've got to work hard because that's who you are.

– Camalot Todd

-

From left: Clark County Manager Yolanda King, Las Vegas City Manager Betsy Fretwell and North Las Vegas City Manager Qiong Liu

LAS VEGAS VALLEY LEADERS

Only 13 percent of all municipal chief administrators — city and county managers, basically — in the United States are women. As of 2015, that percentage hadn’t changed since 1981. But you wouldn’t guess by looking around Southern Nevada.

Three out of four chief administrative officers in the valley are female: Clark County Manager Yolanda King, Las Vegas City Manager Betsy Fretwell and North Las Vegas City Manager Qiong Liu.

The Clark County Commission is majority female — also a rarity among local governments. “If you look around Southern Nevada, in the private sector or government, you see women in higher-level roles,” says King, who has worked for the county since 1986. “That’s good.”

Fretwell, who is leaving in July to become senior vice president of Switch, says that to bring more women into leadership, organizations must provide more opportunities. “As leaders,” she says, “it’s incumbent upon us to really try and create a culture where people thrive.”

– April Corbin

-

B. Rose

BRITTANY ROSE

A Las Vegas musician who showcased her talent at Life Is Beautiful last fall, Brittany Rose hopes to expand to other markets after her new six-song EP drops this summer. She shared some thoughts about being a bi-racial woman in a business dominated by men, and the struggle to be body-positive.

Is it tough being a woman in the music world?

I feel like being a woman in the music world has an empowerment in itself, because you have a voice that people are listening to. You can use that to show how powerful a woman can be. ... I’m definitely not the typical blonde-haired, blue-eyed, tiny girl — that's been a challenge that I’ve come across. … The sense now is that it’s about sexualizing a young woman that’s coming up in the industry. I have friends who are writers that are gorgeous women, but are writing for other people that don’t really have talent because they’re beautiful and can have tons of followers on social media. So that’s something I struggle with every day as a bigger woman, and as a biracial woman.

Sometimes I come to a point where I’m like, I’m never going to look like that — can I push and share my music at the same level? Are they going to want to hear it? But then there are people like Adele and Elle King, that are bigger women and don’t really care and thrive and are powerful, and they’re telling stories.

I’m working on my confidence, but it is so many different women doing it and it gets competitive at the end of the day.

Is that competitiveness good or bad?

Depends on the situation, sometimes it makes you better and hungry and expanded. Sometimes it can hurt a woman as well. I'm sensitive, so it can push you down a little bit. It's about a balance of healthy competitiveness. … It's knowing who you are, being confident and having thick skin. You can't care what people think or say.

Talk a little bit about being a bi-racial woman in America right now

What are you? That's always the biggest question. … I've learned to heighten it. I'm taking pride in it. So, I'll get piercings and tattoos — you want to see different? I'll show you different.

I feel blessed for being bi-racial and thriving in the industry, because that overpowers all the insecurities I have in my weight. And connecting to the African-American side of my family and seeing how they react and then my British side, which is completely different. Mixing those two cultures has been a positive.

Tell me about your song, “Rose Gold.”

It's this woman-empowerment song that I wrote when I was feeling crappy and bad and just went through a breakup. ... I was at home and had just bought this rose gold jewelry, and my best friends commented and said, “Be rose gold.” At first I was like, what should this be about? I started looking up things that describe rose gold, like changes in the light, intensifies with age. Sounds like a woman too.

– Camalot Todd

-

Lyndsay Hailey and the cast of "Magic Mike Live."

LYNDSAY HAILEY

Lyndsay Hailey knows a few things about women — and men. As the emcee of “Magic Mike Live,” the refreshing new male revue at the Hard Rock Hotel, her job is to bridge the gap between the men dancing (and flying) onstage and the gaggles of women screaming with joy in the audience. A comedian and life coach with a mystical side, she feels uniquely prepared to take on the challenge of steering the inventive show, which asks and explosively answers some big questions about female desire and sexuality.

You’re a newcomer to Las Vegas. What are your impressions of the city as a woman?

I have my moments. I remember walking on the Strip for the first time. You just look at your feet and there are the fliers (of escorts). I’ve spent some time in different cities, but I’ve never seen anything like that. If I had been here even five years ago, I don’t know if I would have been able to handle just the environment of Vegas. I think I’m very aware that I’m in Sin City but with a different message.

Let’s talk about that message. What do you hope “Magic Mike Live” achieves?

In a way, the goal is to reverse the paradigm, to flip male revues on their head. But it was really important to (creator and director) Channing (Tatum) and myself and the creative team to not just stop there. We really feel it’s not just leveling the playing field but taking it a step further.

There is a line between appreciation and objectification. That’s the thing. We don’t want to objectify these men. We don’t want to be the female version of the men who’ve harassed and catcalled us. So, what’s the next step up? … I am protective over the men just as men in my role have been protective over women in the past. … It’s about not coming at it from a lower sexual place but a sacred sexual place, respecting men as a god to our goddess.

Have the male performers gotten on board with that approach?

A lot of them have come to me of their own accord, wanting to foster that conversation. To ask, how do I keep it sacred? What does that mean? I can feel when I am going from a place of need or validation versus the expression of authenticity. There’s been some fantastic conversations. I think that’s the purpose of the show — to start asking the questions.

It sounds like you have all put a lot of thought into the show.

In comedy school, we would say, “Assume your audience is the smartest.” Too often people think we need to water it down for the crowds so everyone can understand. I wholly disagree with that. This show is getting such a good response, and in my opinion it’s because we didn’t play to the lowest common dominator. We’re finding that everyone is ready for that. We are making waves, but it’s not anything people didn’t want and weren’t already demanding.

What feedback have you heard?

I just read one (Instagram message) that was, like, “Thank you so much. We thought it would be sleazy and grimy, but everyone left feeling empowered and sexy and as highbrow as something like this can be.” They’re not expecting anything more than a typical revue, and they’re leaving feeling sexually empowered rather than gross.

I’d say there aren’t many productions, especially here in Las Vegas, that leave women feeling like they’ve explored their own sexuality in a genuine way.

It’s been a big focus of the creative team to create a place where women can go into that bubble. It’s sad it’s a bubble. Perhaps it will spread. Maybe one day you don’t have to go to “Magic Mike Live” to feel like this. … One of (Channing’s) big notes for me was, “I want them to go on the same journey as you. Experience the show through you.” There is a moment where I turn into the emcee and I give them permission to do that. And I mean it. I’m on that journey myself. I am truly through this show discovering my own sexual empowerment and finding out what I think is slimy, what I think is empowering, where is our universal line.

Do you think now is the right time for a show like this?

I think culturally we’re in a major shift in consciousness. If we hadn’t done this show right now, I think we’d be behind the eight ball in a matter of months. I feel the world is primed for a takeover with this new understanding.

That’s an optimistic outlook, especially if you look at a lot of news at the national level.

We can look at all that and say, “I’m terrified.” To the best of my ability, I attempt not to do that. I genuinely believe the great resistance comes before the greatest changes, the dark before the dawn. I think men are respecting me more in my immediate surroundings than they ever have. I’m really feeling a reverence from men. So, I could take it outside of myself and look at the global state of affairs and think we’re screwed, but in my personal life I feel more honored and more supported. Trump and all this other crap? When massive amounts of change happen, those threads of darkness hold on even tighter.

– April Corbin