Interactive Slot Machine

Try your hand at the slots while learning the inner workings of the machine and the chances of a win.

Have a Question About Addiction?

Problem Gambling Center executive director Krista Creelman will answer questions about gambling addiction from Las Vegas Sun readers from noon to 1 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 24. Submit a question now and we'll post the answers on Tuesday.

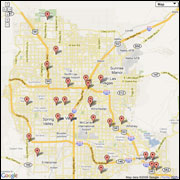

Local Gamblers Anonymous Meetings

See a map to find out about Gamblers Anonymous meetings in the Las Vegas Valley.

20 Questions of Addiction

Gamblers Anonymous offers these questions to anyone who may have a gambling problem.

Share Your Recovery Story

Want to let other Las Vegas Sun readers know your story of recovering from a gambling addiction? Send us your story.

Bottoming Out

Tony McDew not only recognized that he had a gambling problem, but set out to document it with his own video camera, hoping that sharing his experience could help others. When the jackpot hits, "It feels like you're getting high." And when it doesn't? "You want to crucify yourself."

About this series

In the three decades since the psychiatric community recognized compulsive gambling as a mental disorder, it has evolved from a small area of study to a global research effort involving dozens of medical doctors and other specialists who have generated hundreds of studies and hosted as many conferences.

Yet it remains a largely secret affliction, in part because it carries a stigma even here in the birthplace of modern gambling. As a result, sufferers don’t want to discuss the problem or seek help.

Fewer than 10 gambling treatment programs run by state-certified counselors exist in Nevada. The number of nonprofit treatment clinics that waive costs for those who can’t pay — a common predicament for gambling addicts — can be counted on one hand. Fewer than 400 people underwent treatment for gambling problems in state-funded counseling programs in the two-year period ending Sept. 30. Though many more seek out self-help groups such as Gamblers Anonymous, it’s believed to be a fraction of the more than 90,000 Nevadans with gambling problems.

Starting with this story, the Las Vegas Sun explores problem gambling three ways — through the experiences of an addict, by examining what happens inside the brain of an addict, and by considering the role of slot machine designs in feeding gambling addictions.

The stories

- Part 1: Tony McDew not only recognized that he had a gambling problem, but set out to document it with his video camera, hoping that sharing his experience could help others. When the jackpot hits, “It feels like you’re getting high.” And when it doesn’t? “You want to crucify yourself.”

- Part 2: The mere sight of a slot machine can trigger a chemical response in the gambling addict’s brain in the same way the thought of cocaine stimulates a drug addict. Some researchers are exploring the use of drugs to treat addicts. Robert Hunter offers old-fashioned group and one-on-one therapy.

- Part 3: When designer Si Redd realized the overwhelming attraction of his video poker machine, he advised addicts to get help — and leave Nevada if necessary. Today the role of the machine in feeding addiction is debated. At some casinos in Canada, gamblers can tell slot machines to limit their play.

Related Stories

Sun Archives

- LV companies in denial about problem gambling (11-20-2009)

- New courts will stress treatment of gamblers (6-1-2009)

- Criminals could get help for gambling, not prison time (4-18-2009)

- LV attorney who stole $398,345 for gambling habit suspended (2-19-2009)

- Gambling addict’s misery detailed (10-2-2002)

Experts who study gambling addiction remain a long way from knowing why people develop gambling problems. But researchers now know what happens inside the brains of gambling addicts that fuels the addiction, and how best to help them.

A growing collection of research has found that the most afflicted have the kinds of biological brain disorders that are found among drug and alcohol abusers.

Advances in understanding gambling addiction are the result of functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, which allows the brains of gambling addicts, non-addicted gamblers and nongamblers to be scanned and compared.

Before the relatively recent use of MRI machines, scientists could only view people’s behavior, dissect the brains of the deceased or study brain chemistry by drawing fluid from the body. Functional magnetic resonance imaging allows real-time study of the brain by measuring changes in blood flow as well as oxygen levels in the blood.

Scanning participants’ brains as they were shown various gambling-related images or while they gambled with real money revealed a remarkable symptom within the brain:

Dopamine, a chemical that regulates human behavior, including weighing relative rewards and anticipation of those rewards, flooded a part of gambling addicts’ midbrains called the nucleus accumbens. The chemical rush created overstimulated feelings of interest and excitement for the addicts — a reaction that did not occur among non-addicts.

Still unknown — the elusive mystery — is why gambling stimulates dopamine in some people.

Nonetheless, the scans provided the first biological evidence of what treatment providers had long known from working with the hardest cases: For addicts, gambling becomes all-important — eclipsing commitments to family and work. Like scoring drugs and getting high for the drug addict, gambling seems critical for survival.

Economist Don Ross at the University of Alabama and the University of Cape Town, who has studied how society’s reward systems influence human behavior, calls this phenomenon a “hijacking” of the brain’s reward system to create intense cravings and an obsessive focus on gambling.

The brain pulls off this mutiny by figuring out that, if it can identify and connect with an addictive target — say, a slot machine — it can produce its own jackpot — a flood of rewarding dopamine. Triggering that dopamine overflow can overwhelm brain circuits that normally moderate risky behavior, said Ross, a senior economist for the National Responsible Gambling Program, a public-private partnership in South Africa that funds problem gambling research, education and treatment.

These people, Ross says, seek out gambling not for pleasure — which would be a normal reaction to an entertaining pastime — but for the dopamine rush, which in turn creates a vicious circle where the person focuses more intensely on gambling at the expense of everything else.

In Ross’ studies, the dopamine rush among addicted research subjects occurred before any gambling and in response to cues indicating that gambling was about to occur, such as an image of a slot machine or the person’s favorite casino. That result appears to coincide with stories of gambling addicts who — much like the alcoholic who obsesses about wanting to have a drink — are preoccupied with anticipation for gambling.

Blaming her own brain

Carol O’Hare has not had a brain scan, but before she quit gambling, she called herself an addict.

By day, she sold computers, explaining the merits of Random Access Memory and performance speed to moms and dads. After 5 p.m. O’Hare would park herself in front of a video poker machine, medicating herself with the rhythms of choosing and discarding poker hands.

“My logical brain knew I couldn’t outsmart the machine,” O’Hare said. “But my logical brain fell off the track when the first quarter hit the slot. My illogical, addicted brain was driving the bus.”

Suspecting a cocaine addiction, her employer fired her, she said.

“I was like the Valium addict who wanted to make life go away,” she said. “Looking outside ourselves for relief is normal. But repeated attempts to avoid reality could be the beginning of a mental health problem.”

O’Hare would go on to become executive director of the Nevada Council on Problem Gambling, which operates a crisis hotline, in 1996.

Like many people who have wrestled with addiction, O’Hare doesn’t blame the object of her obsession. Rather, she blames her addled brain for the problem.

“If the substance created the addiction, then everyone would become an alcoholic. When I (gamble), triggers go off in my brain differently than for other people. I don’t understand why it happens to me. There could be a genetic component. But the determining factor is me, not the machine.”

Indeed, Ross says even the limited amount of MRI research involving small groups of gamblers indicates that pathological gamblers have a chemical addiction to gambling, which produces in their brains the same kind of “hyperactive dopamine response” found in people who abuse hard drugs.

“For the really chronic cases who must absolutely not gamble, we’ve cracked the code,” he said. “I’ve never seen a study where the problem gambler didn’t look like the cocaine addict. It’s really quite striking.”

Medication may help

Supporting these results is the groundbreaking discovery a few years ago that gambling addicts benefit from medication used for years to treat drug addicts and alcoholics.

One of the most promising is naltrexone, which blocks the release of dopamine and reduces the addict’s cravings.

Psychiatrists Dr. Jon Grant, who codirects the Impulse Control Disorders clinic at the University of Minnesota Medical Center, and Dr. Marc Potenza, who directs the Yale Problem Gambling Clinic at Yale University, are among a small group of researchers pioneering the use of drugs, combined with therapy, to treat gambling addicts.

The use of drugs to combat addiction is so new, Grant said, that no studies have yet compared the relative benefits of drugs and therapy.

“We often don’t know what will help people the most when they walk in the door,” he said. “And people have personal views about things that I think should be respected when they seek help. Some people don’t want pills and others don’t want to talk to a therapist.”

Grant, with a group of research experts from other institutions, is delving into other creative treatment methods besides medication. He co-wrote a recently published National Institutes of Health-funded study that tested a technique called “motivational interviewing” that leads addicts through imagined scenarios ending with the person not gambling.

One scenario might involve a gambler imagining himself driving by a casino without going in. In another, the gambler might go to the casino while repeating mantras that desensitize him to the experience, such as the likely result that he will not win money. Gamblers who participated in six one-hour sessions with a psychiatrist and then listened to tapes at home reinforcing these thoughts gambled less and had fewer cravings than people who simply attended Gamblers Anonymous meetings, the study found.

Much still a mystery

Many problem-gambling experts believe some people are somehow predisposed to addiction but disagree on how much of the problem is genetic versus environmental — which could involve a person’s upbringing, social influences or immediate surroundings, such as the proximity of gambling.

“It’s the $64,000 question: How does someone go from casual to pathological gambling?” said Howard Shaffer, associate professor of psychology in the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of its Division on Addictions.

According to some treatment providers, many compulsive gamblers appear to have poor coping skills. Problem gamblers in treatment commonly tell of turning to gambling as an escape from personal problems, family conflict or psychological trauma, such as the loss of a loved one — while others apparently led happy and productive lives before gambling them down the drain.

Any number of studies have found that compulsive gamblers frequently have other baggage, including abuse of drugs and alcohol, and mood disorders including depression, panic attacks and phobias, without being able to determine cause and effect.

A 2005 study co-authored by Nancy Petry, a psychiatry professor at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine and one of the first recipients of federal funding to study problem gambling, found that problem gamblers were eight times as likely to have a personality disorder as the general population, including obsessive-compulsive disorder and anti-social personality disorder.

Such correlations could have implications for treatment, as people who gamble compulsively because they are depressed could benefit from antidepressants, while treating people for underlying problems such as bipolar disorder could help alleviate gambling binges that were caused by these problems, experts say.

Recent research on the brain and effective treatment methods has far-reaching social and political implications for the field of problem gambling, the casino industry and society at large.

Knowing that addicts are mentally ill rather than simply foolish, spendthrift or morally bankrupt could lead to major changes in the criminal justice system, said Bill Eadington, an economist and director of the Institute for the Study of Gambling and Commercial Gaming at the University of Nevada, Reno.

“If indeed gambling is a disease that could lead to criminal behavior, like drug-related crimes, then putting people in jail might be the wrong approach,” Eadington said.

(Nevada passed a law this year, supported by the casino industry along with problem-gambling advocates, allowing state judges to send criminals with gambling problems into treatment instead of jail.)

Further research on the brain could help separate the addicts who can’t stop gambling from a much larger group of people who binge on gambling from time to time but whose lives aren’t destroyed by their obsession with it, Eadington said. Treatment programs could be mandatory for addicts, while the greater population of binge gamblers might benefit from problem-gambling awareness campaigns and gambling information that’s more targeted to them, he said.

“Addicts should be isolated and protected from the product like diabetics must be kept from sugar. If you’re diabetic we’re not going to give you a half-gallon of ice cream and encourage you to eat it. But in Las Vegas we might be doing that with problem gamblers.”

There’s much about gambling addiction that isn’t known, as many gamblers aren’t helped by the best treatment methods, many others relapse, and brain scan studies don’t tell the whole story about why addicts behave the way they do, said Dr. Potenza, who has conducted some of the few, small-scale brain scan studies available.

And yet the biggest hurdle of all — acknowledgment and an ethical obligation to help the afflicted — has been crossed, at least by people following this still-young field.

A sense of desperation

These newly uncovered theories involving dopamine seem like old news to Robert Hunter, director of the Problem Gambling Center, a nonprofit outpatient clinic dedicated to treating gambling addicts.

There are no pills at Hunter’s clinic — only old-fashioned group and one-on-one therapy.

During a group-therapy session last month, three patients said they had thought about suicide. One man had his arm in a sling after a botched suicide attempt involving a faked rock climbing accident. Another woman introduced herself to the group of 15 or so people with a flood of tears.

“I can’t take this anymore,” she said. “I need help.”

Some attended with urging from friends and family members.

Some said they had gambled a few days ago; others hadn’t made a bet in years but were sticking around to maintain a support network.

Some acknowledged a problem that feels bigger than themselves — too large, perhaps, for any one person to grasp.

“When you say you’re addicted to drugs people say, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry’ and they’re sympathetic. When you say you blew $80,000 gambling, people say, ‘What, are you an idiot?’ ” a man said. “They don’t understand.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy