Sun Coverage

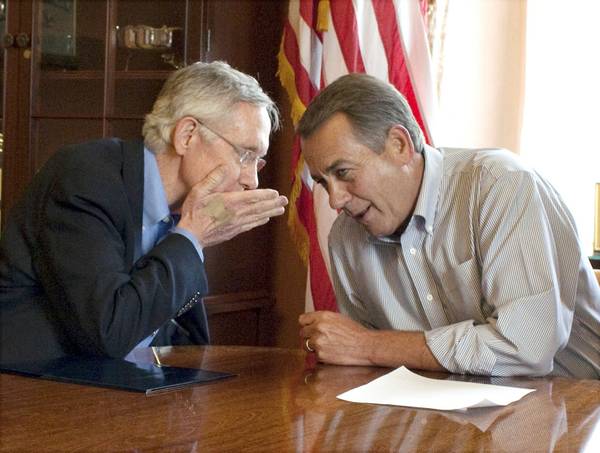

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid released a debt reduction plan he says gives Republicans “everything they want” without harming Social Security, Medicare or Medicaid.

But Republicans, led by House Speaker John Boehner, put out their own plan this afternoon.

Reid and Boehner’s competing plans have similarities: Neither raises taxes, both cut discretionary spending by $1.2 trillion, and both cut more in spending than they call for in a debt ceiling increase.

The main difference is that Reid’s includes additional cuts in mandatory spending to extend the debt limit by another year, and Boehner’s doesn’t. His stops at discretionary spending and takes the government’s borrowing authority only through the next six months.

The time frame is the key sticking point between the parties. Republicans are charging that Democrats are interested only in protecting President Barack Obama’s re-election efforts, otherwise they’d agree to a short-term plan.

“There is absolutely no economic justification for insisting on a debt-limit increase that brings us through the next election,” Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell said this afternoon. “It’s hard to conclude that this request has to do with anything, in fact, other than the president’s re-election.”

But Democrats — backed by market economists and credit rating agencies — say there’s plenty of economic justification for a long-term deal. Without it, the country may temporarily avoid a default, but its credit will likely be downgraded anyway. That would lead to interest rate increases that could hit the country like a tax hike, in everything from their credit card bills to their mortgage payments.

“Congress has already said a short-term solution is not a solution at all,” Reid said. “I hope my colleagues on the other side still know a good deal when they see it. I hope they still know how to say ‘yes’.

“If they now oppose an agreement that met every one of their demands, it will be because they put politics first,” Reid said.

Democrats accuse Republicans of hypocrisy and moving the goal post to score political points.

“Even Republicans rejected a short-term increase in the debt ceiling as recently as last month,” said Sen. Chuck Schumer, citing House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp and House Majority Leader Eric Cantor both recently stressing the importance of thinking big and not taking multiple votes on a debt ceiling increase — the course of action outlined in Boehner’s most recent plan. “Republicans have apparently flip-flopped on this claim. But a short-term deal is still a nonstarter in the Senate.”

House Republicans voted for a long-term increase in the debt ceiling, though in a different context. Their “Cut, Cap and Balance” framework, which received almost the full support of House Republicans, would have raised the country’s borrowing authority by $2.4 trillion — the same figure as Reid’s bill.

But the trade-off there was a constitutional amendment to balance the budget and spending cuts that Senate Democrats have said they won’t support.

Boehner’s plan, which he says “is not Cut, Cap and Balance, but is built on the principles of Cut, Cap and Balance,” poses almost the same terms. In addition to cutting $1.2 trillion from discretionary spending over 10 years, it requires the House and Senate to vote for the balanced budget amendment and adopts Reid’s idea of setting up a joint committee of members of Congress to recommend $1.8 trillion in cuts.

The difference between the plan and the “Cut, Cap and Balance” framework is that the president’s ability to raise the debt limit isn’t predicated on passing the balanced budget amendment, which only has to come up for a vote. But Obama is potentially blocked by another vote — he can only raise the debt ceiling by $1.6 trillion if Congress can agree to the joint committee’s proposal.

Reid’s plan also cuts $1.2 trillion in discretionary spending over 10 years, and strips another $100 billion in mandatory spending by reforming home mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, instituting agricultural reforms, and eliminating waste, fraud and abuse in Internal Revenue Service, Social Security Administration and disbursements of unemployment insurance, and cuts and another $400 billion in interest savings.

But the kicker — $1 trillion — comes from projecting declines in spending that will come with winding down military efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The plan leaves all tax and entitlement issues off the table for now, assigning a joint committee of lawmakers the task of coming up with deficit reductions past the $2.7 trillion in their framework. That committee has to report a plan to Congress by year’s end, just like in Boehner’s bill.

Structurally, Reid and Boehner are engaging in a bit of a do-si-do with these plans. Until he started drafting this proposal, Reid had been advocating the multistep approach, through a framework he set up with McConnell that would have allowed Obama to raise the debt limit in stages. If lawmakers couldn’t amass a veto-proof majority to censure his deficit-cutting proposals, he could go ahead and raise it.

That approach never had the full backing of House Republicans, and McConnell today seemed to be distancing himself from it.

But while the House’s plan adopts a step structure, Democrats say it’s a phony because the president’s ability to raise the debt ceiling in the second step is dependent on action by Congress that isn’t guaranteed.

“We tried to do a real two-step approach yesterday and they said no,” Schumer complained Monday. Boehner “can dress up his plan any way he wants; it is simply a one-step, short-term plan.”

But Republicans aren’t convinced Senate Democrats are playing on the up-and-up, by basing their long-term debt ceiling extension almost entirely on war spending that everyone expects will come down.

“That’s a false number. We know that number’s going to fall down as we continue to withdraw from Iraq and Afghanistan, and we don’t know what the follow-on requirements are going to be,” said Nevada Rep. Joe Heck, a Republican who serves on the Armed Forces Committee in the House. “It’s very easy to grab money that you think we’re already going to be drawing down ... you’ve got to talk about cuts from the baseline, not contingency funds.”

Democrats have an answer to that too: Y’all did it first.

“They have no leg to stand on ... We know the Republicans agree with this math, because they included the exact same savings in the Ryan budget that passed the House,” Schumer said. “They never criticized such accounting then. It’s hard to see how they could do so now.”

Sort of. While the Ryan budget does presume the draw-down in war funding, its pledge to cut $6.2 trillion over the next 10 years is a cut relative to the president's 2012 budget request, Republicans explain, while Reid's trillion dollars in savings estimate is based on current surge-level funding that the president never requested for next year.

"Senate Democrats are employing a budget gimmick that will not fool the credit markets and does not address the urgent need for Washington to get its fiscal house in order," countered Rep. Paul Ryan's House Budget Committee staff in a memo sent out late Monday.

The House and Senate are on course to vote on their independent bills Wednesday; Reid planned to file cloture on his plan in the Senate this afternoon to set it up for a filibuster-proof vote, which he could then call Wednesday at the earliest. Reid hasn’t decided whether he’ll wait for the House to start calling votes on his own plan in the Senate. He needs seven Republicans, assuming he can get the full support of Democrats, to keep the process going, a tall order in a Congress this divided over competing plans.

For now, Reid and Boehner don’t appear to be talking to each other, except through their respective staffs, although they are no longer involved in the intense, compromise-focused negotiations of the past weekend.

Obama is slated to address the nation at 6 p.m. today. When asked if Reid had Obama’s support for his plan, the majority leader said: “Of course.”

Boehner is expected to deliver his own speech on the debt limit to the country following the president's speech.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy