Editor's Note: This is Part One of a two-part series.

He sues all the time but never seems to win. He writes his name countless different ways. Accused squatters say he gave them keys to an abandoned, custom-built house and coached them on what to tell the police if they came knocking.

He calls himself Nana I Am — and he’s at the center of perhaps the most unique and bizarre squatter case in Las Vegas.

Nana teamed with Miguel and Dinora Barraza this year to sue the owners of an abandoned, high-end home in the northwest valley. The trio claimed to be the real owners, sought more than $20 million in damages and said they took possession of the house in 1900 — 105 years before it was built.

Metro Police raided the house a few months ago, arresting the Barrazas on squatting-related charges. They hoped to win the lawsuit so they could live for free in the foreclosed home, according to an arrest report, but Dinora told police they made one payment: Nana got $800 to file the suit.

Squatters have taken over abandoned houses throughout the valley the past few years, but the saga of Nana and the Barrazas is different than most. It’s marked by luxury homes, suspicious real estate transactions, a squatter Cinco de Mayo party, ties to anti-government “sovereign citizens” ideology and lawyer-less lawsuits in which the plaintiffs seek hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars and make nonsensical claims.

“Obviously none of the plaintiffs were alive in the year 1900,” a Metro officer wrote in the Barrazas’ arrest report, adding their lawsuit’s claim that one fraud was perpetrated between 2014 and 1900 “unmistakably does not make any sense.”

At the root is Nana I Am, a mysterious figure who’s been accused of posing as an attorney and of filing court cases, for a fee, to help people stall evictions or foreclosures. Also known as Nana-Amartey-Baidoobonso-IAM, among other variations, he is connected to at least five homes in Southern Nevada: two in the northwest valley, one in the southwest, one off Sahara Avenue about 5 miles west of the Strip and the Barrazas’ former house in North Las Vegas, the Las Vegas Sun found.

But he’s tied to possibly dozens of properties in Southern California, and court records indicate he’s mostly partnered with people who lost their home to foreclosure, not people who moved to abandoned properties.

“I guess he expanded his business to include squatters,” said Huntington Beach lawyer Julian Bach, whose client was sued by Nana.

It’s a ripe market here.

Years after the economy crashed, Las Vegas remains littered with thousands of empty homes, many of which were abandoned during the recession by people with heavy financial problems. And despite the valley’s improved housing market, Metro Police are receiving a rising tally of squatter complaints, with reports from low-income, middle-class and affluent neighborhoods alike.

A black market of sorts took shape — people have broken into vacant homes, changed the locks, drawn up bogus leases and “rented” properties out, often through Craigslist. Stories abound of squatters meeting their “landlords” at convenience-store parking lots to pay their rent in cash and showing bogus rental contracts to real estate agents or police officers who stop by.

An attorney for almost 25 years, Bach says one person who reminds him of Nana is Gilfert Jackson, of Los Angeles. Jackson was arrested in 2009 for allegedly falsely promising homeowners that he could “prevent foreclosures and evictions from their property,” the FBI said at the time. He also was sentenced to prison in 1998 after he allegedly filed more than 200 bogus bankruptcy cases “in a scheme to help renters and homeowners stave off eviction and foreclosure,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

Jackson was “the godfather of this activity,” Bach said. But Nana “really took it to a new level” with lawsuits in federal court and by filing “fraudulent” deeds against properties, even after they were seized through foreclosure.

Nana once sued a client of Bach’s for $25.5 million, but the case was dismissed a few months later. The client later won a countersuit. Bach never met Nana, but as far as he could tell, Nana would find distressed properties and charge people a fee “to delay foreclosures and evictions for as long as possible.”

Metro Lt. Nick Farese of the suburban Northwest Area Command, which received the most squatter calls in Metro’s jurisdiction the past few years, said he had not seen anyone, until the Barrazas, sue to take ownership of a house they were allegedly squatting in.

He figured the Barrazas filed the suit, as well as other cases, simply to “commit crimes and get stuff for free.” The house they sued for — 5464 Sierra Brook Court, near Ann Road and the 215 Beltway — is one of the nicest he’s seen get hit by squatters and had a larger-than-average group of people allegedly staying there.

Metro received calls that 15 to 20 people were in the two-story, six-bedroom, 4,600-square-foot home, which boasts a dual staircase in the foyer, granite countertops and views of the Strip and downtown skylines from the backyard.

“The house was huge,” Farese said.

It’s not the only high-end house in the neighborhood with ties to Nana, either.

When the Barrazas’ group was staying on Sierra Brook, some cars that were seen at the house also were spotted at a foreclosed, 5,400-square-foot home on La Mancha Avenue a few blocks away, a neighbor said. When the Sun visited that house in May, wooden barricades blocked part of its driveway and a sign out front said “WARNING: No Trespass On This Private Land.”

The sign warned of a $5,000 daily fine, said the owners were “Peaceful” and “Law-Abiding,” and declared the home to be “Under 24 Hour Video Surveillance — All Rights Reserved.”

In the lower-left corner, the sign also had Nana’s name and phone number.

• • •

When Nana I Am filed for bankruptcy in 2013, he was no stranger to the courts.

The judge ordered him to show why the case shouldn’t be dismissed. He noted that Nana had filed at least five bankruptcies in prior years, and at least four were tossed from court because he failed to make payments or file required documents. Also, the latest case appeared to be part of a dispute between Nana and a creditor, the judge wrote.

Nana told the court that he was trying to save a church from a supposedly illegal foreclosure. He claimed in bankruptcy papers to have a $500,000 claim against the creditor, Fred Westberg, and that his only debt, at $12,000, was held by Westberg.

The judge, however, dismissed the case and barred Nana from declaring bankruptcy again for about six months.

Westberg had lent money to a commercial-property owner in Los Angeles, foreclosed on the borrower’s building and then had to evict people from it, said Christine Kingston, Westberg’s attorney in the case. But Nana had “no relationship whatsoever” to the people involved in the transaction.

“We don’t even know who this Nana I Am person is,” she told the Sun.

Nana did not respond to requests for comment, and his identity remains, for the most part, a mystery.

Court filings indicate that he lives in the Los Angeles area, and a person who served him court papers in 2012 described him at the time as black, 45 to 55 years old and 200 pounds. In 2013, Nana wrote in court papers that he was single and indicated he had a 10-year-old daughter, Jennifer; a 7-year-old daughter, Light; and a 4-year-old son, Elohim, a Biblical Hebrew word for God. He also wrote that he was a consultant and earned an average of $2,500 per month.

California state records show he registered a business called “America’s Outcry” Enterprises Inc. (sic) as a nonprofit, and a LinkedIn profile says he owns America’s Outcry. “I can help you save your home!” the profile says.

His name and phone number are listed on cancelamortgage.com. “Stop paying mortgage payments on fraudulent loans!” the site declares. A man named Al McZeal runs the website, and he operates another, almczeal.com, that offers “a legal way to keep possession after eviction.”

McZeal and Nana have filed some identical-looking cases. Court records show the same hectic mix of underlined words, bold lettering, varied font sizes and pseudo-legal jargon. They’ve both sought huge payouts, too. McZeal once sued dozens of banks, law firms and others for $246 billion.

They’ve joined forces at least once: In 2012, Nana and McZeal sued 23 banks, mortgage companies and others for $10.7 billion. They claimed one fraud was perpetrated against them “between January 00, 1900 and January 00, 1900.”

Like Nana, McZeal also represents himself in cases he files.

“It has often been said that ‘one who is his own lawyer has a fool for a client,’” the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit wrote in 2008, in a case involving a home in Houston that McZeal purportedly bought while it was heading toward foreclosure. But, the court wrote, McZeal “seems to reject” this notion and helps people “in financial trouble” sue their creditors without an attorney.

The court — which noted McZeal has a “history of filing frivolous complaints” — said he showed “no evidence” that he was the home’s rightful owner.

McZeal, who also has a telecommunications business called Global-Walkie-Talkie, did not respond to requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Nana also is connected to the Vision of Faith Hope, an entity that provides no clear sense of what it does and where it operates.

In one section of its website, the group says its main offices are in Seattle but notes “we also have two other post in Africa and Middle East” (sic). It adds that the group has worked since 1993 to “eliminate poverty and provide emergency relief, rehabilitation, and development activities in Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia, and other surrounding countries.”

But in another section, it says its goal with “every action” is “to build community through a vibrant Louisiana nonprofit sector.”

The website does not appear to list any staff members or Nana’s name. But his email address and phone number — the same L.A. number that’s included in many of his lawsuits — are listed in the “Contact us” section.

Above all, Nana’s name itself is an enigma.

It’s unclear what his real name is, and the Sun found only one hint that it’s something other than Nana I Am: A 2011 court filing by Nana says he was formerly known as “Allen Hart Jr. Cesti Que Trust.” The phrase “cestui que trust” means someone is the beneficiary of a trust.

His usual moniker is written numerous ways in his own court papers, with different punctuation, spelling, spacing and word order. They include Nana “I AM,” Nana A. Baidoobonsoiam, Nana Baidoobonso and Nana Amartey Baidoobonso-“I AM.”

Nana has been sued at least three times in recent years, court records show, but one in particular offers a window into his alleged operations.

The case, filed in 2012 in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Southern California’s San Fernando Valley, claimed that Anita Rios and her husband, then facing foreclosure, learned of a TV commercial that claimed to help people keep their homes.

They called and were told to meet at the offices of Diamond Real Estate in Downey, Calif. While there, representatives told them Nana was a lawyer and “an expert in handling foreclosure-related matters in bankruptcy courts,” Rios alleged.

The couple hired Nana to help with their bankruptcy filings and paid $2,000, part of a $3,500 retainer, the lawsuit claimed. But the representatives later told the couple that Nana could only be an observer in the case, and at the first meeting of creditors, he “attended as a spectator but refused to provide any assistance.”

In a court filing by all of the defendants except Nana, the group said they never told the couple that Nana was an attorney, were surprised he collected money for legal services and “only mentioned” that Nana “could help in their situation but did not know to what extent.”

“The only individual who is responsible for these acts is Nana-Baidoobson-Iam” (sic), they wrote.

Diamond lawyer Grace White said in a court filing this year that Nana “just happened to be in the office that day and represented himself to be a lawyer to all defendants and plaintiffs.”

But, she wrote, Nana was not an attorney and filed their bankruptcy anyway, and the couple lost their home to foreclosure.

“The only party who received any monies,” she wrote, “was Mr. Baidoobonso.”

White did not return a call seeking comment, and a call to Diamond’s listed number also was not returned.

Kingston, the creditor’s lawyer, never met Nana. But she suspects he offers to help save people’s homes from foreclosure, for a fee, and the main goal is probably to “buy them time” as they file cases in various court systems.

Their filings “screw things up so royally (that) nobody knows what the heck just happened.”

"It's ridiculous," she said.

Rios’ lawyer, Jerome Zamos, said there was a “bigger kind of phenomenon” going on.

People facing foreclosure get pitched by groups offering to help: Nana allegedly claimed to be an attorney; others say they’re real estate experts or sponsored by various groups; and others have claimed to be part of Donald Trump’s organization, Zamos said.

“At the end of the day,” he said, “they’re all scams.”

Prosecutors have charged some people, he said, but “why haven’t they gone after the rest of them?”

David Lopez, head of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office real estate fraud section, says there is a “cottage industry” of people who target distressed homeowners with supposed lifelines but merely scam them.

He said there used to be a bigger number of “organized rings” out there — his office once worked a case that involved nearly 1,000 properties in Los Angeles County alone. But now, amid an improved housing market and smaller inventory of distressed homes, scams are typically run by individuals.

He said Nana wasn’t unique but that police and prosecutors in Los Angeles were aware of him, as people have complained about him to Los Angeles County’s consumer-affairs department.

Lopez declined to say whether Nana has been investigated, but added: “He’s on the radar of local authorities.”

• • •

Searching Nana’s names in court databases did not reveal any indictments against him. Las Vegas police, however, are aware of him.

Metro Officer Jose Martinez wrote in the Barrazas’ arrest report that Nana and Miguel and Dinora Barraza were suspected of forgery. According to the report:

• Miguel initially told police he was renting the house on Sierra Brook and had known Nana, the purported landlord, for eight years but would not describe what Nana looked like or what kind of job Nana had. He said Nana gave him the keys to the house, and he admitted a bank owned the property, not Nana.

• Judith Barraza — who, according to court records from another case, is Miguel's daughter — admitted their lease for the house was bogus and that Nana coached her on what to say if the police showed up.

• Dinora told police they hadn’t paid rent or a deposit for the house. The only money they spent, she said, was $800, which was given to Nana to file the lawsuit.

• When Martinez asked Dinora why they took over someone else’s house, she said they were presented with the opportunity to possibly get a free home. She said they talked it over, it looked good, and “they did not think about the consequences,” Martinez wrote.

Asked who Nana is, Lt. Farese told the Sun that he couldn’t comment.

“It’s part of an ongoing investigation,” he said.

Metro officers had raided the house May 11, arresting the three Barrazas and a man named Robert McMinn Jr. on squatting-related charges.

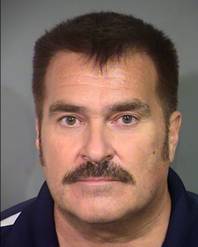

Robert McMinn

Dinora Barraza

Miguel Barraza

They are scheduled to appear in Las Vegas Justice Court on July 26. Court records do not show an attorney for them.

A phone number for McMinn could not be found. When the Sun called Dinora Barraza’s phone number, a woman answered and then passed the phone to another woman. When asked for comment from the family, that woman said, “We don’t want interviews.”

She hung up when the Sun asked for her name.

• • •

After defaulting on his mortgage, Erasto Alcantar lost his home in Oxnard, Calif., to foreclosure. But he allegedly refused to leave, and he went to court to fight for the property — with Nana I Am.

Nana and Alcantar teamed up in 2011 to sue real estate companies, the Oxnard Police Department and an Oxnard officer who threatened to arrest Alcantar if he tried to re-enter the home. They alleged wrongful foreclosure and breach of contract, seeking $900 million for “intentional infliction of emotional, mental, physical and psychological stress.”

“This lawsuit is yet but another example of a homeowner who … has been foreclosed upon, evicted and then commences frivolous litigation, alleging all types of ‘illegal’ and ‘wrongful’ acts … throwing everything but the kitchen sink up on the wall to see what sticks,” attorneys for some defendants said in a court filing.

A federal judge dismissed the suit a few months after it was filed.

Since 2009, records indicate, Nana has filed at least 37 lawsuits in federal and California state courts. They often involved foreclosed homes that other people owned — usually the same people he sued with. In more than a few cases, his co-plaintiffs allegedly stayed in their home after foreclosure and faced eviction.

His lawsuits can be dubious at best — he'll claim a foreclosure was illegal but doesn’t really show why — but look ludicrous given the piles of money he tries to get. Nana has sought $468 million in one case, $700 million in another and $900 million in at least three more, court records show.

Nana has sued alone and doesn’t seek enormous payouts in every case. Moreover, the Sun could not confirm how he found the people he sued with or how they found him. But, it seems, his cases usually fizzle, sometimes because he disappears after filing them. For example:

• In 2009, Nana and Ramon Aguirre sued for a house in Altadena, Calif. They sought to take ownership and at least $100,000 in damages, but the suit derailed after their $350 check to file the case bounced. The judge gave them another chance to pay, but he dismissed the case after they failed to do so.

• In 2012, Nana and Blanca Cardenas sued for a Los Angeles duplex that she lost to foreclosure. They sought $25.5 million in damages — they also wrote $900 million — but a judge dismissed the case a few months later, saying Nana and Cardenas “repeatedly missed or ignored deadlines and court orders” and “failed to participate in their own litigation.” They filed the suit Feb. 17. According to a story in LA Weekly that didn’t mention Nana or the lawsuit, Cardenas was arrested Feb. 22 for trespassing at the property and deported to Mexico a week later.

• In 2013, Nana and Otilia Luna sued for a Los Angeles home. Luna and her husband lost the property to foreclosure that year but “failed to vacate” and faced eviction, court papers say. Nana and Luna sought $42 million and claimed they still owned the house, but a judge dismissed the case less than two months after it was filed.

Efforts to reach several of Nana’s co-plaintiffs, including Alcantar, Aguirre, Cardenas and Luna, were unsuccessful.

Mark Carlson, a lawyer in the Oxnard case, never met Nana. But, he told the Sun, he figured Nana was “trying to eke out a living by getting people to pay him a little bit of money to file these things and then get a settlement here or there.”

Carlson had a prior run-in with him, at least on paper. After Nana sued a client of his in 2010, Carlson obtained court approval deeming Nana a “vexatious litigant” in California, meaning Nana thereafter had to get a judge’s approval before he could file cases in state court.

Nana had filed several cases that were “shams” and “frivolous” and were intended to “hide properties” facing foreclosure, Carlson said in court papers.

• • •

Nana seemed to have a change of heart toward Carlson’s client in the 2010 case, brokerage firm Boardwalk Properties of Long Beach, Calif.

Boardwalk owner Mike Potier did not respond to requests for comment. But in a typo-riddled email to him enclosed in a court filing, Nana wrote that he looked at Potier’s card “and saw a symbol on it which made me realized that you are a man of God just like me and started feeling bad. So I deceided that I call you this morning, talk to you, and get to know you and drop my law suit.”

Nana wrote that his “anger and frustration is not towards you per say, but the lender who took our property illegallyand put my family out and collected the insurance money.”

“It is so said that because of GREED and SELFISHNESS of a hand full of people at the top has desecreated our economy. … And my prayers everyday is calll onto God The Belovd Almighty I AM Presence to release his Almighty Powers into action and blast and annihilate, desolve and consume and remove from trhis earth, all those individuals who are determined to desercrate Americas economy and destiny.”

Nana added that he and Potier “are brithers in Christ and we are suppose to love and teach others to do good deeds and not to hate. But money is the root of all evil and some of us choose to sell their sole for it.”

“All what I ask from you,” he added, “is to give me and my cusin at least 3 weeks or less to relocate.”

On Friday, Part Two will focus on the Las Vegas homes that are tied to Nana and the Barrazas.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy