It happened before terrorists rammed planes into the World Trade Centers, before the recession rattled Southern Nevada and before Zappos triggered urban revitalization by moving its company headquarters to downtown Las Vegas.

Back in the late 1990s, Las Vegas city planners began devising a vision for how they wanted the city to look two decades down the line.

The timing made sense, given the start of a new millennium and the city’s explosive growth — a 73 percent population increase — in the preceding decade.

The grassroots-style planning process involved a survey and input from community leaders, homeowners, architects, land-use attorneys and planners, all tasked with answering this guiding question: “How can growth be accommodated while enhancing the city’s quality of life and livability?”

The group’s answers appeared in the “Las Vegas Master Plan 2020,” which the City Council adopted in September 2000. Essentially, the plan created a framework to help shape policy — and, in theory, enable the vision to become reality.

“By 2020, Las Vegas will become a multicultural and diverse community where people and families are our top priority, where we can live and grow together in safe and distinctive neighborhoods,” according to the plan’s vision statement. “Our people will achieve their highest potential in education, employment, business, recreation, and arts and culture. We will have a fully developed sense of pride in our desert environment, our history, our community, our future and our variety of citizens while promoting a high and sustainable quality of life and economy for all.”

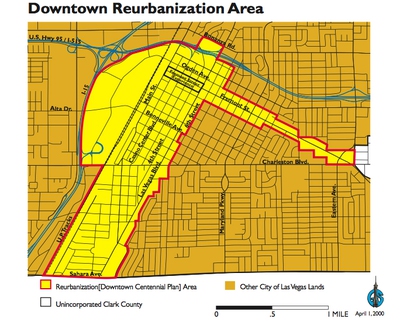

In 2000, the city also approved a downtown-specific plan, which serves as a subset of the overarching master plan. Today, the City Council may vote on an updated version of the downtown plan that would chart the vision for the city’s urban core through 2045.

The city also is in the beginning stages of embarking on an update of the citywide master plan, which expires in 2020. The revitalization of downtown played heavily in that report, setting the stage for the downtown-specific plans.

“It’s meant to be a blueprint,” said Robert Summerfield, who leads the city’s long-range planning efforts. “It does kind of have a visionary or wish list feel to it quite often.”

So how close is the city to achieving the vision set forth in the 2020 master plan, especially as it relates to downtown? It’s a mixed bag, but many of the wanted elements are at least in progress.

The “Las Vegas Master Plan 2020” includes dozens of policies aimed at achieving certain goals. Here’s a look at some of them:

Policy: That each district be focused on a central open space, park, public facility or landmark that lends itself and character to that district.

This concept remains a work in progress. While city planners often use the term “green space,” the vision encompasses a much broader range of possibilities, such as increasing trail networks, pocket parks and plaza space, Summerfield said.

The city wants to create more open space downtown featuring benches and decorative landscaping that would invite people to meet and spend time there, he said.

Still, there’s an obvious lack of parks downtown. A draft of the new downtown plan calls for a central park and eight to nine neighborhood parks, a community sports park and a sculpture park. That’s in addition to mini parks fashioned out of underused spots in dense urban areas.

“There’s a major shortage (of parks) downtown,” said John Curran, real estate portfolio manager for the Downtown Project. “There’s only so much they can do.”

Curran was involved in the creation of the city’s first “parklet,” built in a 120-square-foot parking space the city donated to the effort. Near 6th Street and Carson Avenue, the mini park featured shade, a table, seating and chess and checkers boards, he said.

“We’d love to see a massive park built, but the economic realities are … how are you going to buy land and build a park?” Curran said.

Policy: That the Fremont Street Experience continue to be the focal point for tourist and gaming activities within the downtown. An important secondary node for existing and future tourist and gaming activities should be the area north of Sahara Avenue and south of St. Louis Avenue, west of Las Vegas Boulevard.

The first part of this policy is certainly true and, in fact, understated. The area surrounding the Fremont Street Experience has become a major gathering spot for locals seeking entertainment — not just tourists and gamblers.

The Downtown Project, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh’s $350 million investment that includes a real estate component, independent venture fund and small businesses, is largely to thank for the rejuvenation downtown particularly along East Fremont Street.

When Zappos relocated its headquarters from Henderson to downtown Las Vegas, it triggered a wave of new restaurants and bars, some of which the Downtown Project helped fund. Today, places like the Container Park, Gold Spike, Bunkhouse and numerous eateries lure people downtown.

“It’s been a pretty dramatic transformation,” Curran said.

As the Fremont area surged, however, the area north of Sahara and St. Louis avenues mostly stagnated. In the draft of the updated downtown plan, the latter area is termed the “Gateway District.”

“Honestly, I think we did expect a little more interest in (that area),” Summerfield said. “However, the city has some expectations to do some upgrades on Las Vegas Boulevard. We think with those upgrades, there will be more of an interest.”

The upgrades, which hinge on funding, include widening sidewalks, improving traffic-lane configurations and storm-water drainage, updating light fixtures and adding trees, he said. The Las Vegas Boulevard improvements would run from Sahara to Owens avenues.

Policy: That the city pursue the development of a performing arts center within the downtown area.

Done. The Smith Center for Performing Arts, a public-private partnership many years in the making, opened in 2012.

A car rental fee provided a hefty dose of the money needed, and the city kicked in the land, infrastructure and environmental cleanup to make the project possible. The Donald W. Reynolds Foundation also donated $150 million to the effort.

The performing arts center sits in Symphony Park, a 61-acre site downtown that also houses the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health and the Discovery Children’s Museum.

The recession hampered other growth expected within Symphony Park, such as residential and office buildings, Summerfield said.

“It’s meant to be and it’s still anticipated to be a very mixed-use district,” he said.

In terms of housing, developers are showing interest in bringing mid-rise residential buildings to the area, he said. The city continues to pursue other development opportunities for office and retail space, he said.

Policy: That the city explore the potential viability of a major sports entertainment center for the city of Las Vegas.

Former Mayor Oscar Goodman has made no qualms about his desire to bring a major-league sports team to Las Vegas. He even indicated it was his one piece of unfinished business when he left office in 2011.

His wife — current Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman — has continued championing the cause. With Carolyn Goodman now in her second term as mayor, the city still isn’t home to a major-league team, but that’s not for lack of trying. Among the higher-profile proposals was to build a publicly subsidized $200 million soccer stadium in Symphony Park, a project that fell apart in 2015 when the MLS rejected a bid from Las Vegas to locate a franchise in the city.

City officials, over the years, have been involved in discussions to bring professional teams for hockey, soccer, baseball and, more recently, football to Southern Nevada. A few of those plans called for an arena or stadium within Las Vegas city limits.

The city still serves as home base for the Las Vegas 51s, the Triple-A affiliate of the New York Mets, who play at Cashman Field downtown. The 51s’ owners want to move the team to a new stadium in Summerlin — a scenario that has prompted numerous discussions about the redevelopment of Cashman Center. The most likely outcome is anchoring the site with a new sports facility, perhaps soccer, with mixed-use development surrounding it, city officials have said.

The 51s’ contract to occupy Cashman expires in 2022.

Talks about building a 65,000-seat football stadium and bringing the Oakland Raiders here, however, have dominated recent headlines. The Las Vegas Sands Corp. and Majestic Realty Co. are backing the stadium project, which would need $750 million in public funding.

The Southern Nevada Tourism Infrastructure Committee is vetting plans for the stadium, which is proposed for a 42-acre parcel along Tropicana Avenue, near Koval Lane. UNLV owns the land.

Even if a major sports facility winds up being built in unincorporated Clark County, supporting facilities, such as training fields, could end up within Las Vegas city limits, officials said.

Policy: That entertainment activities, such as movie theaters and live performing arts, be developed within the downtown, to serve both a local and regional population.

Las Vegas Councilwoman Lois Tarkanian remembers a time when she wouldn’t have walked downtown alone. Empty lots with tumbleweeds and trash dominated the landscape into the early 1980s, she said.

Now, she regularly hears her grandchildren planning whole days and nights downtown.

“The progress has been made by people who are believers and people who have the passion and the perseverance to work on this,” she said. “We have some very good people here in Las Vegas who really love this city.”

Bars and restaurants have popped up along East Fremont Street and in the Arts District, providing locals a reason to head downtown. The Smith Center for Performing Arts offers a similar draw.

Downtown’s entertainment options continue to evolve. One example: Construction is underway for Eclipse Theaters, a three-story cineplex at Third Street and Gass Avenue. It’s expected to open in September.

Policy: That the city cooperate with the Regional Transportation Commission, other valley entities, other levels of government and private sector investors to develop fixed guideway transit systems.

In 2000, the term “fixed guideway transit system” generally referred to high-capacity bus service, Summerfield said. The dedicated Regional Transportation Commission bus lanes downtown — on Casino Center Drive and Grand Central Parkway — are an example of that vision.

Nowadays, city officials view the term in a much broader sense, including to describe bus rapid transit, modern streetcars or light rail, he said.

The RTC has been studying the possibility of bringing light rail to Las Vegas, but funding remains a barrier. In March, about 50 people from Las Vegas, representing both the public and private sector, traveled to Denver to learn about that city’s light rail system.

“I think fixed guideway is much more prevalent in our conversation about transportation planning than it ever has been before,” Summerfield said.

Today, the Department of Public Works will present a citywide mobility plan to the City Council. The plan focuses heavily on making improvements for pedestrians, but it also looks at possible future investments related to high-order transit, Summerfield said.

Policy: That the city support policies and programs related to addressing the needs of, and reducing the number of, the local homeless population.

Homelessness remains one of the region’s biggest problems since the Great Recession, said Deacon Tom Roberts, president and CEO of Catholic Charities. Demand for services has increased greatly since then, he said.

When Roberts arrived at the agency in 2012, Catholic Charities was providing shelter for about 200 homeless men each night, Roberts said. Now, the nonprofit shelters about 500 homeless men nightly.

Catholic Charities’ food pantry also serves about 100 families each day.

“That number is going up, not down,” Roberts said.

The key to reducing the homeless population, he said, lies in providing adequate mental health and substance abuse resources, which would address the underlying issues many of these people face. Roberts said he has been working with local officials to encourage more action in that regard.

“It’s big. It’s complicated. It’s expensive,” he said of the problem. “We need mental health resources and assets in this downtown corridor. This is where the population is. If we can treat them while they’re in this corridor, we have a much better chance of getting results.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy