“They used to be looking to see if this was a suitable site. Now they’re looking to see how they can make it suitable. That's the big shift,” said U.S. Rep. Dina Titus, D-Las Vegas, who has been active in opposing a Yucca Mountain repository for more than 30 years. The Nuclear Waste Policy Act passed in 1982, and a 1987 amendment sealed Nevada’s fate as the sole dumping ground for the nation’s high-level radioactive scrap. Sort of.

The “Screw Nevada Bill” has never been resolved. Upon the federal designation of Yucca Mountain — about 90 miles from Las Vegas — as the only viable site for storing many thousands of tons of dangerous waste, the state Legislature passed a law making such storage illegal. Led by formidable former U.S. Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., a generation of lawmakers and residents have fought and feared the realization of a vision into which the country has already sunk an estimated $15 billion. Despite that massive investment, Reid and former President Barack Obama successfully derailed the Yucca plan, starving it of funding and withdrawing its license application.

Critics say seismic activity and infiltrating water make Yucca Mountain unfit, without even considering the timeworn infrastructure that would be used to transport waste across the country. Scientists don’t agree on the risks over thousands of years, which is why supporters call for the project to move forward if only to invite more study.

“We’ve been studying it for 35 years; you don’t need to probe it anymore,” Titus said. “They know that there’s a moving water table, they know that there are faults out there ... there’s no more probing that they need to do.”

The president of the United States begs to differ. Donald Trump’s March budget request to restart the licensing process for Yucca Mountain was $120 million. While the budget carrying into this fall leaves out that funding, Titus thinks Yucca has momentum, citing Energy Secretary Rick Perry’s recent visit to the site. Perry, the Energy Department and several federal agencies were sued by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton for failing to fulfill a federal mandate to establish a permanent repository for nuclear waste, and his message to Nevada leadership was vague yet clear: “The state of Nevada has helped keep America strong, safe and secure since the earliest days of the Cold War. I look forward to the state of Nevada maintaining its leadership role in America’s safety and security.”

Even in retirement, Reid minced no words in reinforcing his old mantra that Yucca is dead. “The Republicans have to understand that they’re not about to do this. ... They can play games, but it’s through. Yucca Mountain will always be a hole in the side of a mountain. That’s all it is.”

Nevertheless, debate is heating up again in Washington, D.C. Draft legislation seeking to push the project forward came up for discussion in a House of Representatives subcommittee last month. All but one of the lawmakers in Nevada’s congressional delegation are conversely pushing for local consent when it comes to storing nuclear waste.

“Now that (Yucca is) back on the table,” Titus said, “we’ve got to be sure that people have the information and can be motivated to fight against it.”

–Yvonne Gonzalez

NEVADANS ARE NOT UNANIMOUS

When Dan Schinhofen first started learning about the Yucca Mountain project in 2005 as a Pahrump resident, he never expected to become a leading voice on the subject.

“It wasn’t on my bucket list,” said Schinhofen, who now sits on the Nye County Commission and spearheads the area’s push for restarting consideration of “the sole candidate site for the nation’s first high-level civilian nuclear waste repository,” as the county website puts it. “We’re not advocating for Yucca Mountain. We’re advocating for the science to be heard.”

While most state officials stand opposed to any further evaluation of Yucca Mountain, Nye County joins eight other rural Nevada counties and U.S. Rep. Mark Amodei, R-Carson City, in supporting the project’s renewed momentum under the administration of Donald Trump.

Nevadans on Yucca Mountain

In a poll of 700 residents last May, the majority was opposed. The survey, commissioned by the nonprofit think tank Center for Western Priorities, found that 51 percent were more likely to support a candidate who would block the project, 26 percent said a candidate’s stance wouldn’t affect their vote, and 23 percent were less likely to support the candidate. Voters from all parties followed this trend.

Nye County stands to benefit financially from Yucca Mountain if it were to be found safe and constructed. In previous years when the project was under active consideration, the federal government provided the county up to $5 million per year. Construction and operation of a Yucca Mountain facility could produce a windfall for an area without much other significant economic development.

“If it’s safe, who would say no to a multigeneration, multibillion-dollar project?” Schinhofen said.

Dr. Michael Voegele worked as part of a team of scientists charged with determining if tens of thousands of tons of spent nuclear fuel safely could be stored deep beneath ground at the Yucca Mountain site. Voegele, who worked on the Department of Energy license application to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, previously worked as a consultant for Nye County and joins Schinhofen in advocating for a continued Yucca process.

“The NRC reviewed the work that we did and thought that we did a good job,” Voegele said. “The program was stopped by an administration that did not follow the law.”

Hope for a restart of the long-debated program grew with Reid’s retirement and the election of Trump, who along with Energy Secretary Rick Perry acts favorably toward Yucca Mountain. Trump’s first budget request included $120 million toward restarting the project.

In an ideal situation, Schinhofen said, Yucca Mountain would receive a full scientific vetting — something project opponents feel sufficiently has happened, but Nye County supporters do not.

“We’d follow the law, we’d have the hearings, the science is vetted per the NRC and then we’d find out if it’s safe to construct,” Schinhofen said.

In past years, some politicians and local officials have advocated that Nevada negotiate for the best deal possible in exchange for accepting the project. Speaking on behalf of the county, Schinhofen could not peg what a potential compensation figure might look like. “There’s no number I could land on to say give us $50 million up front and give us $10 million a year.”

–Adam Candee

-

Dawn at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, Jan. 19, 2017.

LEGISLATIVE APPROACHES TO RESOLVING YUCCA MOUNTAIN GO HEAD-TO-HEAD

Nuclear Waste Informed Consent Act: Permits the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to authorize a waste repository only if the secretary of energy obtains written consent from the governor of the host state and affected local governments, as well as Indian tribes. If the act passed, Yucca could only be revived with such approval. Despite the governor and all but one member of Nevada’s congressional delegation opposing the dump site, this option would allow further discussion and potential study of Yucca Mountain if supporting rural counties were able to gain traction.

Nevada’s Democratic U.S. Reps. Ruben Kihuen, Jacky Rosen and Dina Titus have signed onto the consent act. Titus, the primary sponsor, said it reflected recommendations from the Obama administration’s Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future.

U.S. Sens. Dean Heller, R-Nev., and Catherine Cortez Masto, D-Nev., have sponsored a similar Senate measure. In a letter to Energy Secretary Rick Perry, Heller wrote: “This open process ensures all Americans have a meaningful voice in the process if their community is being considered for a future nuclear waste repository. Rather than attempting to force the failed Yucca Mountain proposal on Nevadans, U.S. taxpayers’ dollars would be better spent on further implementing your agency’s past efforts on consent-based siting. This worthwhile initiative will ensure that no state will be forced to accept nuclear waste against its own will.”

U.S. Rep. Mark Amodei, R-Carson City, has not signed onto the consent act and says Congress and the Department of Energy should make the Yucca site a center for research as well as reprocessing.

“While some of my colleagues in the delegation have successfully managed to slow the project through the congressional appropriations process, I do not believe it is a ‘dead’ issue and think it is more likely the repository will eventually come to fruition through a sound scientific process over time,” Amodei has said in the past.

Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 2017: Bypasses barriers to advancing Yucca by giving more control over air and water permitting to the federal government, as the state has blocked certain permits in the past. In addition, the bill eliminates the current requirement that the federal government make progress on siting a second repository and the capacity cap for Yucca of 70,000 metric tons of waste. Bill supporters say Nevada’s “technical objections” would be assessed and addressed through the long-awaited movement on the licensing process.

“Our goal here is to identify the right reforms to ensure we can fulfill the government’s obligation to dispose of our nation’s nuclear material,” U.S. Rep. John Shimkus, R-Ill. and chairman of the Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Environment and the Economy, said during an April meeting.

Shimkus points to the billions paid by utility ratepayers in states that produce nuclear energy to develop Yucca Mountain, with little progress made over the decades. Opponents contend the draft legislation doesn’t provide enough time during the licensing process for Nevada’s more than 200 contentions to be heard.

Steve Frishman, consultant for the Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects and Attorney General’s Office, says the bill also attempts to address a pretty unprecedented problem: committing to a century of appropriations for one specific project. He said it would allow Yucca funding to skip cyclical congressional approval. “This has always been seen as a problem,” Frishman said. “Congress runs hot and cold on this project at various times.”

–Yvonne Gonzalez

-

Protesters of the proposed Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository and weapons testing lie on the pavement after crossing the line into the Nevada Test Site in Mercury. During the spring 2003 demonstration, 34 people were arrested for trespassing.

CONCERNS SURROUNDING YUCCA MOUNTAIN

In 2010, just as Yucca Mountain was going dormant, John D’Agata’s “About a Mountain” was released. The nonfiction book looked at the proposed repository in terms of possibility as well as probability, the scientist’s go-to lens on risk. “In its own studies for Yucca Mountain, the Department of Energy considered ‘reasonably foreseeable incidents’ during the shipping of its waste to Yucca, but not the ‘worst-case credible’ ones,” D’Agata wrote, sharing the DOE’s resulting estimation of a 1-in-10 million chance of a serious accident unleashing the radioactive waste. “Yet, when it comes to a place like the city of Las Vegas, where nine deliveries of nuclear waste could be arriving every day, those 1-in-10 million odds over a 40-year period are more accurately represented by a figure of 1-in-27,000 odds, thus making the probability of a nuclear accident in Vegas higher than the possibility of striking it rich in a casino.” The author echoed Rutgers University sociologist Lee Clarke in contending that it was dangerous to concentrate so much on probabilities, as “things that have never happened before happen all the time.”

Transporting nuclear waste to the site

How much waste could travel near Las Vegas?

Spent uranium in the fuel rods remains radioactive for thousands of years and must be stored in casks with special shielding. As many as 110 trainloads could travel near Las Vegas per year, and up to two trucks could travel near the city per week.

Serious risks come with shipping high-level nuclear waste to Nevada, especially because much of the nation’s stockpile would come from across the country by rail and highway, increasing the field of potential contamination substantially. Industry publication E&E News wrote that rail cars could run near the Trump International Hotel on the Strip, though no route has been finalized. Other concerns include handlers and drivers being exposed to radioactive materials and the possibility of an accident releasing radioactive materials into the environment.

Groundwater pollution and erosion

The federal government initially argued that Yucca Mountain served as a suitable geologic formation for nuclear waste storage because arid conditions would prevent water from traveling quickly through its infrastructure. Regulations for siting nuclear repositories required the government to disqualify sites if groundwater flowed through the environment for any period under 1,000 years. The worry always was that water could corrode the storage containers, thus releasing radioactive materials into the environment and the groundwater. However, in 1996, Department of Energy researchers discovered an isotope known as Chlorine-36 at Yucca Mountain. It is significant because Chlorine-36 was first introduced into the atmosphere with nuclear testing conducted in the Pacific Ocean. This suggested, as several Nevada scientists had warned, that water traveled through the mountain more rapidly than expected. In response, the DOE said it would install titanium “drip shields” around the waste canisters to prevent materials from bleeding into the mountain.

Seismic activity causing leakage

Nevada officials and opponents of Yucca have long argued that the siting is unsuitable because the mountain rests on earthquake faults. The state says this could pose risks during the emplacement phase and after the waste has been stashed away in the mountain. Fault movement, for instance, could affect the water table and geologic structures, leading to the release of radioactive materials. The DOE and some unaffiliated scientists disagree. They acknowledge that Yucca Mountain sits on several fault lines, but they contend that the tectonics are not powerful enough to create an earthquake that would affect the repository. In the past, the department has adjusted its plans to avoid one of the major fault lines.

One alternative to storage

Nuclear reprocessing recovers some spent nuclear fuel for reuse. The process is used in Japan and in Europe, but it has been slow to catch on in the U.S., in part because of the cost, which could raise electricity rates or further burden the country’s atrophying nuclear industry. In 2012, the Blue Ribbon Commission said the move was premature “given the large uncertainties ... about the merits and commercial viability of different fuel cycles and technology options.”

Terrorism and security risks

An unsettling national security concern is tied to the Yucca plan. Does a known waste repository turn Yucca Mountain into a terrorist target? Proponents say storing the country’s spent nuclear fuel in one place is better than the current system, where fuel is widely distributed. Opponents question that logic, wondering whether it’s prudent to create what could be a terrorist target 90 miles outside of a city whose economy is heavily reliant on tourism. Other concerns include destruction of a transportation cask en route by explosives or a shoulder-fired missile; theft of radioactive material from a nuclear power plant, which could be used to create a “dirty bomb"; a cyberattack on a nuclear reactor, which could result in the release of radiation and also disrupt the power grid.

Age-related impacts

Once emplaced, nuclear waste at Yucca Mountain would slowly decay over hundreds of thousands of years, making it difficult to predict long-term health risks. Scientists differ, first noting that a leak would not look like the classic cartoon interpretation of neon liquid seeping out of the mountain. It would be in a solid, stable form by the time it reached the repository. One scientist told tech publication The Verge that the material would be so stable that he’d be comfortable storing a waste canister in his backyard. Others worry about even low-dose radiation.

–Daniel Rothberg

A recent cautionary tale

On May 9, about 200 miles from Seattle, part of a storage tunnel collapsed at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Railcars full of radioactive waste were inside, but Washington’s Department of Ecology detected no escaped radiation. Yucca Mountain opponents pointed to the incident as a warning of what could happen in Nevada if the central repository proposed decades ago were built here, while supporters suggested such a scare could have been avoided if the vision for Yucca had been realized.

Hanford reportedly is the largest depository of radioactive defense waste, as it made plutonium for nuclear weapons for decades, including the bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, at the end of World War II. In a 2010 story about the Obama administration withdrawing Yucca's license application, the Seattle Times said the move left the fate of the “Manhattan Project’s nastiest goop” up in the air.

In April 2016, one of Hanford’s old waste tanks sprung a leak. Wired magazine reported that workers had been shuffling radioactive material from tank to tank as they waited for two things to happen: 1) Yucca Mountain to begin storing waste, and 2) an onsite vitrification facility to turn waste into glass logs for safer storage and eventual transport to Nevada’s repository. The latter facility is expected to launch by 2032, though it and Yucca both were originally slated for completion in 1998.

–Erin Ryan

-

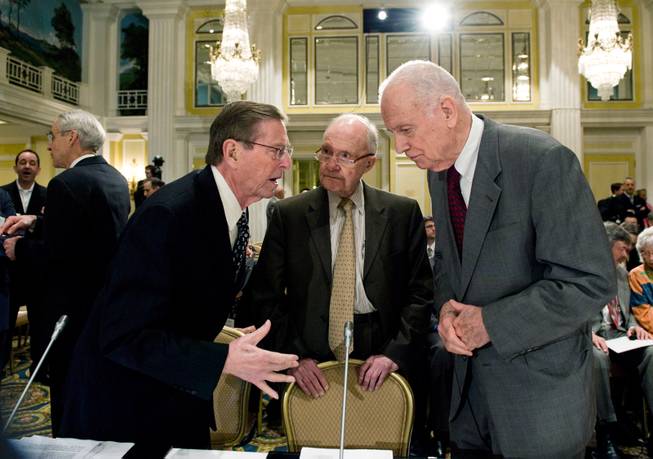

Lee Hamilton, right, and Brent Scowcroft, center, co-chairs, Blue Ribbon Commission on America's Nuclear Future Agenda, talk with former New Mexico Sen. Pete Domenici, Thursday, March 25, 2010, during the group's meeting in Washington.

BLUE RIBBON COMMISSION RECOMMENDATIONS

At the request of then-President Barack Obama, the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future was formed to review policy and recommend a new strategy for managing “the back end of the nuclear fuel cycle.” The group met more than two dozen times between 2010 and the release of its final report in 2012, after hearing testimony from experts and stakeholders, visiting waste-management sites here and abroad, and conducting five public meetings.

1. Consent: The report indicated that forcing a federally mandated fix over the objections of a state would “take longer, cost more and have lower odds of ultimate success.” The commission said localities should volunteer to be considered.

2. Oversight: Given the overall record of public mistrust in the DOE and the federal government, the commission recommended that Congress charter an independent federal body to oversee waste management.

3. Funding: Since 1982, nuclear waste disposal has been paid for by utilities and their ratepayers. Yet those funds often are “inaccessible to the waste program.” The commission said it shouldn’t have to compete for its own funds.

4. Options: The report asked the federal government to develop a deep geological repository. It noted that the U.S. would “need to find a new disposal site even if Yucca Mountain goes forward,” because of the quantity of waste.

5. Storage: Interim storage sites for waste could allow spent nuclear fuel to cool before being transferred to a permanent repository. They also would allow nuclear power plants to fully decommission, rather than store rods indefinitely.

6. Transport: The report called the current transfer system “excellent,” but said regulations should be updated with developments in nuclear fuel, as greater need and demand for moving waste would reveal new public concerns.

7. Innovation: Members of the commission agreed that more research and development was needed in the country’s nuclear energy sector, especially in the creation of “a regulatory framework for advanced nuclear energy systems.”

8. Policy: The report said the U.S. should lead the world on safety, nonproliferation and preventing the weaponization of nuclear energy. “Longer term,” it said, “the U.S. should support the use of multi-national fuel-cycle facilities.”

–Daniel Rothberg

-

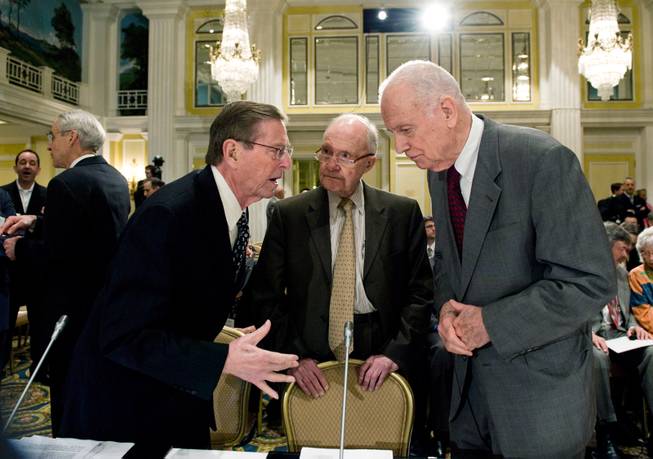

Congressmen, including Jerry McNerney, D-Calif., left, and Rep. John Shimkus, R-Ill., second from left, tour Yucca Mountain, Thursday, April 9, 2015, near Mercury. Several members of Congress toured the proposed radioactive waste dump 90 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

WHAT WOULD HAVE TO HAPPEN TO ENABLE WASTE STORAGE AT YUCCA?

Even if Yucca Mountain were green-lighted, the federal government would have to develop another deep geologic repository for storing nuclear waste, the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future found. The panel wrote in 2012 that “the U.S. inventory of spent nuclear fuel will soon exceed the amount that can be legally emplaced at (Yucca Mountain) until a second repository is in operation.” In 2014, the most recent year with available data, the U.S. Department of Energy estimated that the nation had about 70,500 metric tons of heavy metal in need of disposal. Industry lobbying group the Nuclear Energy Institute puts the current figure at 78,590 metric tons, whereas Yucca Mountain can store only about 70,000 under the current cap. Other hurdles the project would have to overcome:

New office, old plans

Restarting the project would be an administrative challenge, said Judy Treichel, executive director of the Nevada Nuclear Waste Task Force, which was formed in response to the state being chosen as the nation’s nuclear waste dump after the 1987 amendment to the Nuclear Waste Policy Act.

Did you know?

There are now more than 2 million documents associated with the Yucca Mountain proceeding.

“Before you ever get to licensing, there’s no department at the Department of Energy, there’s no division for a Yucca Mountain project,” Treichel said. “They would have to begin again to put together what used to be the Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management.”

Steve Frishman, consultant for the Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects, agreed with Treichel that any plans for Yucca Mountain would need to be revisited now that so many years have passed.

“That tunnel has just been sitting there,” Treichel said. “There’s probably a lot of mold (and) degradation ... there’s probably corrosion.”

Frishman said rockfall may be an issue, though likely not at the level of the recent tunnel collapse at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in the state of Washington.

Transportation

Another hurdle would be laying out the route the waste would take to Yucca Mountain. Treichel said the originally proposed rail route cuts through land that is now the Basin and Range national monument, though the Trump administration issued an executive order to revisit the use of the Antiquities Act in recent monument designations.

Did you know?

According to the World Nuclear Association, near-surface and deep-geologic repositories — such as Yucca Mountain — are commonly accepted options for permanent storage of high-level waste. But here are a few the U.S. has explored and abandoned over the years: launching waste into space; embedding it in ice sheets; sealing it in underground boreholes where it would build up heat and melt the rock around it before cooling and crystallizing the radioactive material into the rock matrix.

Treichel said that because of their need to be built near robust supplies of water, most nuclear power plants are far from the Yucca site.

“It’s a true test for our failing infrastructure, because you suddenly have thousands of miles of transport required with the heaviest possible loads — that’s why it has to go (primarily) by train,” she said.

Frishman said the old rail-line plan, which lost its Bureau of Land Management easements, would have required building 300 miles of new tracks. He said officials needed to modify both the license application and the environmental impact statement to move forward.

Licensing and legal challenges

Plan updates would come before any foray into licensing, Treichel said. If officials got that far, the project would still face legal challenges and hundreds of contentions.

Frishman said two lawsuits filed by the state of Nevada are being held in abeyance, both getting at the standards by which a license application would be judged.

“So if they restart the licensing process, the first thing the state of Nevada is going to do is reopen both of those lawsuits,” he said.

The licensing process alone would take years, with an estimated 400 days needed just to address hundreds of objections raised over the years by groups, including the state.

Frishman said contentions were addressed much like in civil court, where a panel would consider testimony from both sides for each one before making a decision.

Construction

If licensing approval were secured, Frishman said the commission would then need to issue a construction authorization, which is essentially the disposal decision.

He said the licensing application indicated that construction and initial waste disposal would take more than two decades. The repository is designed to handle 3,000 metric tons of waste per year, Frishman said — 1,000 metric tons more than what is currently produced by reactors each year.

The repository could be open for 100 years after the first placement of waste, Frishman said. After that, an amendment would need to be submitted to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to close it. “We’re just at the very, very, very first step of a 100-year process.”

–Yvonne Gonzalez

Other states with a lot at stake

While the fight over Yucca Mountain continues, high-level waste is being stored across the country at reactor sites and others licensed by the federal government to watch over the sensitive material.

Nuclear fuel rods last two to three years in a reactor before the fission process uses up enough of the energy in the uranium that they are no longer efficient. During that process, they become radioactive and intensely hot. Spent rods first go to “wet storage” in indoor cooling pools. Once they’re heat-stabilized after a period of one to five years (or longer), they’re transferred into "dry storage" in heavy-duty casks that shield radioactive material for up to a century (a full setup can weigh 280,000 pounds, most of the weight coming from the metal and concrete cask). As plants have accumulated more and more rods, they’ve modified storage racks to pack them in much tighter, but this is not a permanent solution.

Interim storage sites are being explored. According to the NRC, two entities have expressed interest in applying to build interim sites, one in Texas and the other in New Mexico. If these applications are approved, the NRC will issue licenses valid for up to 40 years.

Especially given how much has been invested in waste disposal by utility ratepayers in areas producing nuclear energy, these states have a lot at stake as the nation tries to settle on a way forward:

Illinois: 10,180 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel

Pennsylvania: 7,330 metric tons

South Carolina: 4,680 metric tons

New York: 4,180 metric tons

Alabama: 3,840 metric tons

North Carolina: 3,760 metric tons

California, Florida, Georgia, Michigan and New Jersey all hold more than 3,000 metric tons.

Arizona, Connecticut, Texas and Virginia all hold more than 2,000 metric tons.

Arkansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, Ohio, Tennessee and Wisconsin all hold more than 1,000 metric tons.

Eleven other states range from the low end of 30 metric tons (Colorado) to 790 metric tons (Missouri).

–Ric Anderson and Chris Kudialis

-

Radiation sign next to Red Forest in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation, Ukraine.

WARNING SIGNS FOR THE FUTURE

One lingering issue with Yucca Mountain or any other permanent repository for nuclear waste is how to communicate what it is to future generations, maybe 100 years from now, maybe 10,000. Linguists have argued over how best to present this information. What message can transcend English and last for 10,000 years? How do you convey the unseen threat of radiation?

About 40 years ago, the Department of Energy began tackling this problem with a panel of experts known as the Human Interference Task Force. They proposed using markers — triangular pyramids of granite — with three central markers that contained symbols and writing in multiple languages to convey the message that nuclear waste lay there. The panel hoped that the symbols and messages would resonate because they would be passed down through oral transmission.

While the Yucca Mountain project languished, the government funded a second study of nuclear semiotics in 1992. In a report prepared by the Sandia National Laboratory, another panel of experts convened to suggest how to mark the Waste Isolation Pilot Project in New Mexico. The message should connote visual and verbal messages, they concluded.

First, ominous earthworks would be laid out in areas to demarcate the site. One design they suggested was a field of metal spikes. Another suggested design included dagger-shaped earthworks. These berms will guide visitors to a message area that communicates messages both linguistically and non-linguistically. Rudimentary information would be shown through faces indicating horror, such as the haunting figure in Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” That would be accompanied by written words that the panel hoped would convey this: “This place is a message … and part of a system of messages … pay attention to it! Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture. This place is not a place of honor ... no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here ... nothing valued is here.”

–Daniel Rothberg

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy