Seven years ago, a group of elementary school teachers launched an after-school program for fifth-graders. It was so successful and beloved by the students and their parents that they wanted it extended to sixth grade. Then seventh. Then eighth. And ninth.

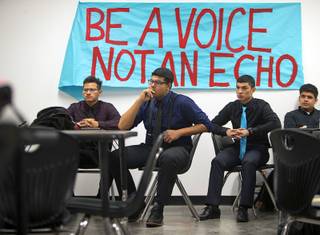

After five years of bouncing around borrowed space within the Clark County School District, the after-school program known as Scholars Working OverTime — or SWOT —evolved into its own charter school on Bonanza Road near Lamb Boulevard in the northeast part of Las Vegas. It is believed to be the first charter school in the state proposed and launched by a group of existing public-school teachers.

Now known as Equipo Academy, the college preparatory school is set to graduate its first senior class of 36 students this year. Thirteen of the seniors have been with the program since its inception; the majority of the rest came aboard a year or two later.

All 36 are expected to have college as an option waiting for them after they receive their diploma. Even with such a small senior class, a 100 percent graduation and college acceptance rate will be a notable achievement for the institution.

That’s because Equipo does not consider grade-point average, attendance or academic merits during its admission or re-enrollment process. Siblings of current students are admitted first to keep families together. Then, students who live near the school are admitted. After that, any student who applies is eligible for acceptance. If there are more applicants than open spots, seats are awarded by lottery. The goal is to embrace any type of student.

Principal Ben Salkowe and Director of College Access Rachel Warbelow believe every child is reachable and it’s never too late to get them ready for college.

“We’ve had people not be invested (when they start),” Salkowe said. “They didn’t know much would be required. There have been a lot of come-to-Jesus moments. But I’ve never had a kid see all the chips lined up (to go to college) and then say they didn’t want it. Every student gets on track. They can love school.”

Added Warbelow: “Parents want better. Kids want better.”

But a desire for success is different from an understanding of how to achieve it. Equipo guides its students and their families. Traditional public high schools are typically in session roughly six hours, from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m. or thereabouts. Equipo students typically stay an additional three hours.

Tutoring is offered every day for those who need to catch up academically.

Administrators remind students of upcoming college deadlines, help them choose schools and double-check applications. One night, the school staged a potluck dinner and assisted families in filling out federal financial aid forms.

Halfway into the academic year, the current college acceptance rate for Equipo seniors is 86 percent — most to UNLV and UNR. Also represented are colleges in Wisconsin, Arizona, California and Washington. Every time a student receives notice of acceptance, an announcement is made to the entire school during lunch.

Warbelow believes the announcements motivate the students — not just the seniors, but also the younger students who might not have college graduates in their own circles to look up to.

“It’s like they are celebrities,” she said. “You’ll hear them say, ‘Oh! I met her once!’ ”

Senior Michael Carranza said the personalized attention has made all the difference for him as a student. After spending seventh through ninth grade with the after-school program, he spent two years at a traditional public high school. He felt overlooked. When ACT exams rolled around his junior year, he realized he wasn’t getting the help he needed and made it his mission to get back to Equipo.

“I didn’t want to be at Las Vegas High School graduating on a giant football field. I’m thankful (I went back to Equipo). I would have fallen off the deep end, but they really care here,” he said.

Michael has since been accepted to Nevada State College. He dreams of holding a well-paying job in business administration or computer science, and he joked about someday returning to the academy to teach a course in “what not to do as a teenager.”

His mother, Sonia Carranza, acknowledged the difference Equipo has made in her son’s life. She believes that outside of parents, schools play the biggest role in motivating and supporting children, and that the teachers and staff at Equipo go above and beyond.

“I feel like they’re not teachers just as a job,” she said. “I feel like they’re teachers because they really enjoy helping the kids. I like that they focus so much on helping, because it’s not the same in every other school.”

Salkowe credited the success of Equipo so far to his dedicated staff and the early support SWOT received from the school district, particularly the principal who green-lit the program and then-Superintendent Dwight Jones, who supported the expansion. Salkowe believes trusting teachers and giving them autonomy leads to great results.

Enrollment at Equipo is capped by the legal occupancy levels of its building, which is the former home of a construction union. There are 684 students — 314 in high school and 370 in middle school. Salkowe would like to see his school grow and affect more families. The wait list for the school is about 250. But he is also acutely aware that scalability could be an issue, and he doesn’t think the approach of Equipo could work for every student or community.

For Salkowe, it’s not so much about the macro-level educational system but the specific students he sees and mentors every school day.

“We made a commitment to those fifth-graders,” he said. “We just had to see that through.”