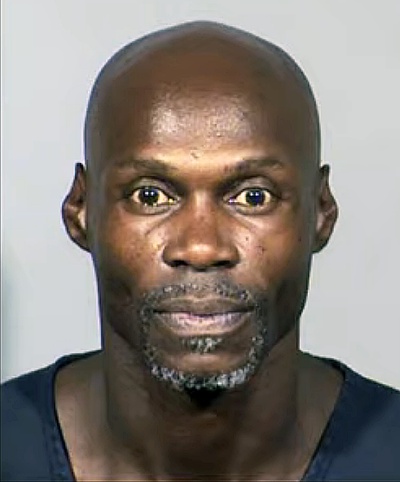

On their own, heart disease, scarred lungs or methamphetamine could’ve killed Byron Williams the morning he died in Metro Police custody. But being cuffed behind his back as he lay on his stomach uttering “I can’t breathe” for the 24th time as officers awaited an ambulance contributed to his death on Sept. 5, 2019, a medical examiner who conducted his autopsy testified Friday during a public fact-finding review.

The hearing, held after the Clark County District Attorney’s Office made a “preliminary determination” that the officers will not face any criminal charges, took place at the county's government building chambers. It aimed to more thoroughly brief Williams’ loved ones and the public on what occurred when he lost his life.

Metro subsequently outlined policy changes put into place following the in-custody death.

Related content

Williams’ family was not convinced the hearing amounted to transparency.

“The lack of complete information and the disrespect from their unwillingness to deal openly with us makes it impossible for our family to heal,” Williams' niece, Teena Acree, wrote in a statement released through the family’s attorney. “These officers' actions were deplorable! Their callous treatment of our Ronnie was inhumane! They must be held accountable. We want accountability and justice.”

"Metro continues to hide behind their supposed investigation of the officers to hold back the full facts, videos and reports from the family of Byron Williams,” wrote attorney Bhavani Raveendran. “This is unacceptable. This fact-finding hearing is just the start of transparency, and more steps need to be taken.”

Family members and local activists have expressed outrage about lapses of footage from body-worn cameras and the officers’ lax behavior during the arrest.

They’ve alleged that if Williams hadn’t been Black, they wouldn’t have “hunted and chased" him down over the minor infraction of not having lights on his bike. At the one-year anniversary of Williams’ death last month, attorney Antonio Romanucci said that lawyers were preparing a wrongful death lawsuit against Metro. The family is also being represented by Benjamin Crump, a prominent civil rights attorney.

Without knowing Williams’ medical conditions and illicit drug intake, it’s unlikely the pair of officers, who saw him pedal away and run and climb walls in an effort to evade arrest, could’ve known that a fatal chain of events had begun.

Dr. Jennifer Corneal said that Williams had suffered a heart attack he might have not noticed 12 to 24 hours before his death, or as soon as four hours prior. He also had pulmonary fibrosis — scarring of the lungs.

His compromised lungs had to work harder to help Williams breathe, Corneal said, and running would have aggravated that condition.

The amount of meth in his blood was in the “lethal range,” Corneal said. Williams’ body had superficial cuts and scrapes, she added. There was no internal trauma. She declared his death to be a homicide, meaning somebody else's actions contributed to the death.

Clark County Chief Deputy District Attorney Michelle Fleck questioned Corneal and Metro Detective Scott Mendoza on behalf of the state, while attorney Joshua Tomsheck was appointed as an ombudsman who spoke on behalf of the family.

Mendoza also walked the hearing attendees through previously unreleased footage of the arrest. Williams, who had a monitoring ankle bracelet, had violated house arrest and had the officers checked his name, he would’ve come up as arrestable. However, the officers didn’t know that before they tried to pull him over.

Riding in a Metro cruiser before dawn, Officer Benjamin Vasquez and Officer Patrick Campbell spotted Williams riding a bike near Martin Luther King Boulevard and Bonanza Road. His bike had reflectors but no lights, which are required under city ordinance.

When they tried to stop Williams, he took off before ditching his bike and scaling a couple of walls before giving up at a nearby apartment complex.

Immediately, as they were trying to cuff him, Williams is heard saying he can’t breathe. One of the officers, also out of breath, noted that it must have been because of the foot chase.

As Williams continued to complain about his breathing, he is told that the officer restraining him only had a knee on his buttocks, which the footage shows. Williams’ breathing wasn't compromised in that position, Corneal said.

Five more officers and a sergeant showed up and Williams was stood up and taken to an area near Metro cruisers. As Williams was standing, he appears to drop a pill case with pharmaceutical opiates and a baggie of white powder that tested positive for meth, Mendoza said.

During the arrest, the officers joked that Williams had “incarceritis,” a term police use that Mendoza said means to fake a medical condition to avoid a jail cell. An officer joked about Williams’ Nike sneakers and how they might fit another officer.

Once Williams appeared unconscious, an officer checked his pulse and breathing.

At different times, the officers turned off their cameras, such as when an officer who took off with evidence he was transporting to a substation, and another who drove to the hospital.

One of the policy changes now requires officers to leave their cameras on until the call is cleared.

“In hindsight,” the officers should have taken Williams’ pleas more seriously, Mendoza conceded when questioned by Tomsheck.