The Stewart Indian School campus in Carson City is a tranquil place today, a postcard-like setting with handsome stone buildings, towering cottonwood trees and well-groomed commons.

But beneath the institution’s surface beauty lies a starkly cruel heritage. Stewart, one of more than 350 institutions of its type in the United States, was founded with the mission of destroying Native American culture by forcing the assimilation of young Indigenous people into white culture. It’s a place where children were confined, strictly forbidden from speaking their tribal languages or participating in their customs, forced into manual labor, punished harshly for rules violations and isolated from their parents for years on end.

Untold numbers died at Stewart and elsewhere, as the world was stunned to learn with the discoveries of more than 1,000 unmarked graves of children at boarding schools in Canada this summer.

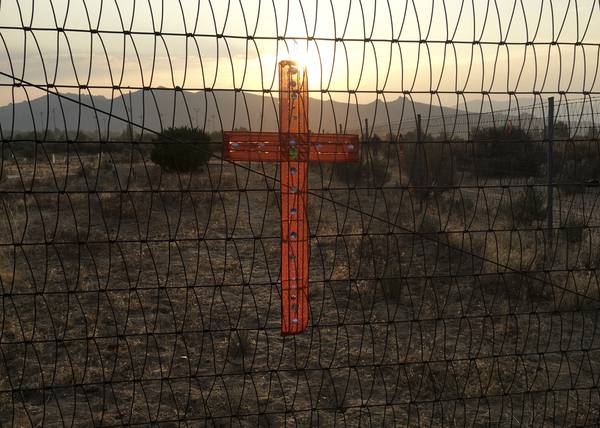

This month, Northern Nevada teen Ku Stevens did his part to raise awareness about Stewart and other Native American boarding schools when he led a 50-mile, two-day Remembrance Run from the school to the Paiute reservation near Yerington.

It was a remarkable display of leadership from a budding young Native American social advocate, and now Nevada lawmakers should follow Stevens’ example by focusing more attention on Stewart and increasing state support for Nevada’s Indigenous peoples.

Stewart closed as a school in 1980 after 90 years of operation, and today its administrative building has been converted into a museum and cultural center. (Other buildings on the campus house Nevada state government offices, including the Nevada Indian Commission and Department of Corrections offices.)

The museum and cultural center is a rich asset for Nevada, as one of few places in the nation that offers a comprehensive and culturally respectful story of boarding schools.

The facility unflinchingly recounts Stewart’s traumatic past but presents a narrative that ends triumphantly with students and their families ultimately defeating the government’s campaign of forced assimilation. In addition to artifacts and modern touches like video displays, the museum offers an impressive array of research materials such as yearbooks, school records and transcripts of interviews with survivors.

It’s something worth seeing for all Nevadans, especially our youth, for the same reason that German schools make it a policy to take students there through concentration camps or Holocaust museums. American children need to see the horrors of our past so as not to repeat them.

Currently, the Stewart museum and cultural center operates with a small staff, and could use an education coordinator due to increased interest from schools for tours after the discoveries in Canada. Lawmakers should fund that position and take steps to facilitate more school tours.

Meanwhile, state legislators should be looking for new ways to use state resources to directly benefit Nevada’s Native Americans.

Too often, states pay too little attention to Indigenous populations, and instead stand aside and point to the federal government for help.

That shouldn’t happen in Nevada, which is home to more than 30 separate Native American tribes and colonies, and where Clark County has one of the fastest-growing Native American populations in the country.

State leaders, in setting their priorities, should include finding ways to put the power of state government to work for these communities and individuals. Why not explore funding a state commission to study issues concerning the rights and opportunities of Native Americans living off of reservations, for instance? Or fund a curriculum that teaches students across the state about Native Americans in Nevada and elsewhere? Or find a way to support research and counseling for historical trauma? Is there a way for the state to augment or support the development of affordable housing in Native American communities in the wake of the $10 million in federal American Rescue Plan funding that was directed to those communities for that purpose?

The possibilities for state efforts abound, but the road to progress starts with state leaders concentrating on the needs of Nevada’s Indigenous peoples and not simply looking to the federal government to provide resources.

Ku Stevens, with his actions earlier this month, helped shine a light on Stewart and open a door to discussion about the generational trauma caused by Native American boarding schools. It’s an issue that has touched most Indigenous families, including Stevens’ own — his run retraced the route his great-grandfather took in escaping Stewart more than a century ago.

Stevens, an elite track athlete who plans to attend the University of Oregon, told a crowd of more than 150 at the beginning of the run that it was because of the courage and perseverance of his great-grandfather and others like him that Stevens and his generation were able to observe their Native American culture and traditions today.

It was a powerful message that should resonate with Nevada’s state leaders.